• NBA All-Star 2025: Complete coverage

• Get NBA League Pass TODAY >

The NBA didn’t arrive in the Bay Area until 1962, long after the big East Coast cities were already hoop-established. Economics were in play even back then when Eddie Gottlieb, owner of the Philadelphia Warriors, was given an offer to sell that he couldn’t refuse: $850,000.

So the Warriors made a Gold Rush to the Bay, extending the league’s boundary, and fast-forward to now: It seems basketball has been here forever.

Because:

- The Bay had both Wilt Chamberlain (who arrived with the Warriors and stayed three years) and Bill Russell (raised in Oakland and schooled at the University of San Francisco).

- Rick Barry managed to play for the ABA and NBA without leaving, hooping for the Oakland Oaks and two incarnations with the Warriors, helping them win a championship.

- Lots of fans claim to “believe” when their beloved home team is faced with an improbable task, but only those who willed the 2006-07 Warriors in the playoffs actually did.

- Outside of Boston and LA, name another place with more NBA championships. (You can’t.)

- And while the Bay certainly didn’t invent basketball, Stephen Curry changed it.

From San Francisco to Oakland and a few surrounding spots in between, the game didn’t just find the Bay — the Bay found basketball and embraced it ever since.

That’s why the 2025 NBA All-Star Weekend is not only a celebration of the league but its connection — helped by the Bay Bridge — with two shores that combined their resources to create a basketball destination.

Oakland emerged as fertile ground for talent, specifically East Oakland, which gave birth to dozens of NBA players and a sprinkling of Hall of Famers. Meanwhile: Silicon Valley money built an arena in San Francisco, giving the Warriors a billion reasons to move — while sticking around.

A place this big and rich with hoops history needs a road map to tell the story and explain Bay … sketball. It’s time, then, to take the tour:

The houses of hoop

The Chase Center has served as the Warriors’ home since 2019.

Chase Center, San Francisco. It’s the “House That Steph Built” and soon Curry will have a statue at the courtyard entrance. When it was completed in time for the 2019-20 season, the current home of the Warriors and site of the 2025 All-Star Game revitalized a sleepy waterfront segment of San Francisco called Mission Bay, now a busy (and pricey) neighborhood.

The move from Oakland was saluted as a return to roots as the Warriors’ first home was San Francisco. But the team resisted any urge to return to the San Francisco Warriors name, in part because of its affection for Oakland.

Chase Center is undeniably upscale and plenty of wealthy techies occupy the choice seats, which you might expect. Still, the arena has hosted an NBA champion (2022) and at least as long as Curry is around, the basketball will be worth the price.

Cow Palace, Daly City. The still-standing first home of the Warriors was, in the 1960s, an entertainment hub. Located just south of the city limits (the parking lot is actually in San Francisco), the “barn” hosted The Rolling Stones, The Beatles and the 1967 NBA All-Star Game (where Barry was the MVP). The primary tenant was the rodeo, hence the name.

Chamberlain wasn’t a fan and remarked how, as he was about to jump center one night, a raindrop caused by a leaky roof stabbed him in the eye. He also said the place reeked of livestock, while Barry called it “a rat hole.”

By 1975 the Warriors had moved to Oakland. A scheduling conflict — an ice show called the “Ice Follies” (which featured Sesame Street characters on ice skates) booked several dates at the Oakland Arena — caused their NBA Finals against the Washington Bullets to get bumped to the Cow Palace. They swept the Bullets in an upset, but imagine that happening today.

Oakland Coliseum Arena. It was an odd place to hold so many championship moments because, for much of its pre-Curry existence, the arena saw lots of losing basketball. And it sat not in the middle of a bustling city, but an industrial area wedged between the freeway and the BART subway, next to the Oakland A’s stadium.

But, what memories: The Warriors won four titles (including 1975) while calling it home, and the amount of water tossed about by “the Splash Brothers” (Curry and Klay Thompson) washed away all previous basketball sins. That said, the arena was effectively shut down by Kawhi Leonard and the Raptors, who won the final game ever played there when Toronto clinched the 2019 title.

About the redundant name Coliseum Arena: It changed to Oracle during its peak and is now simply the Oakland Arena. And with the A’s having moved on, the arena and stadium largely sit empty, free of tenants.

Relive some of the best moments in the history of Oracle Arena.

Where they got schooled

Archbishop Mitty High School (San Jose) The city to the south doesn’t have a rich history of producing NBA players, but one managed to not only crack the code, but thrive — Aaron Gordon. And in 2021 he added “NBA champion” to the Mitty alumni profile.

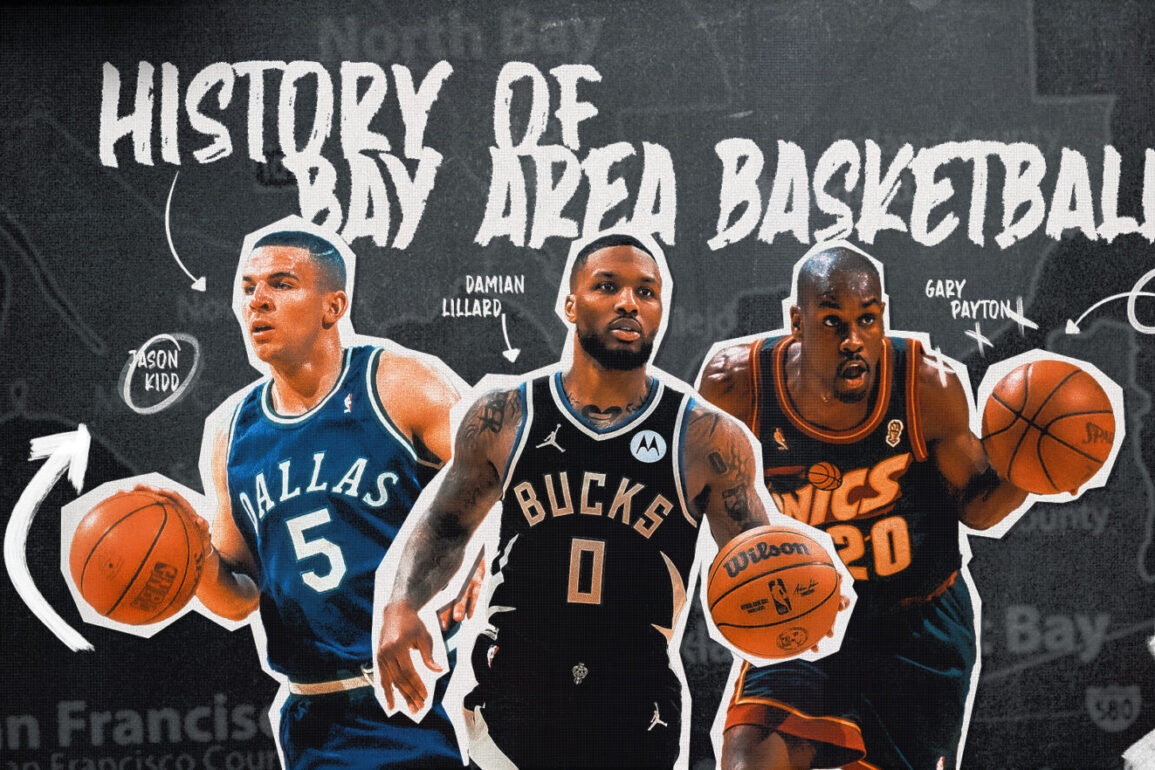

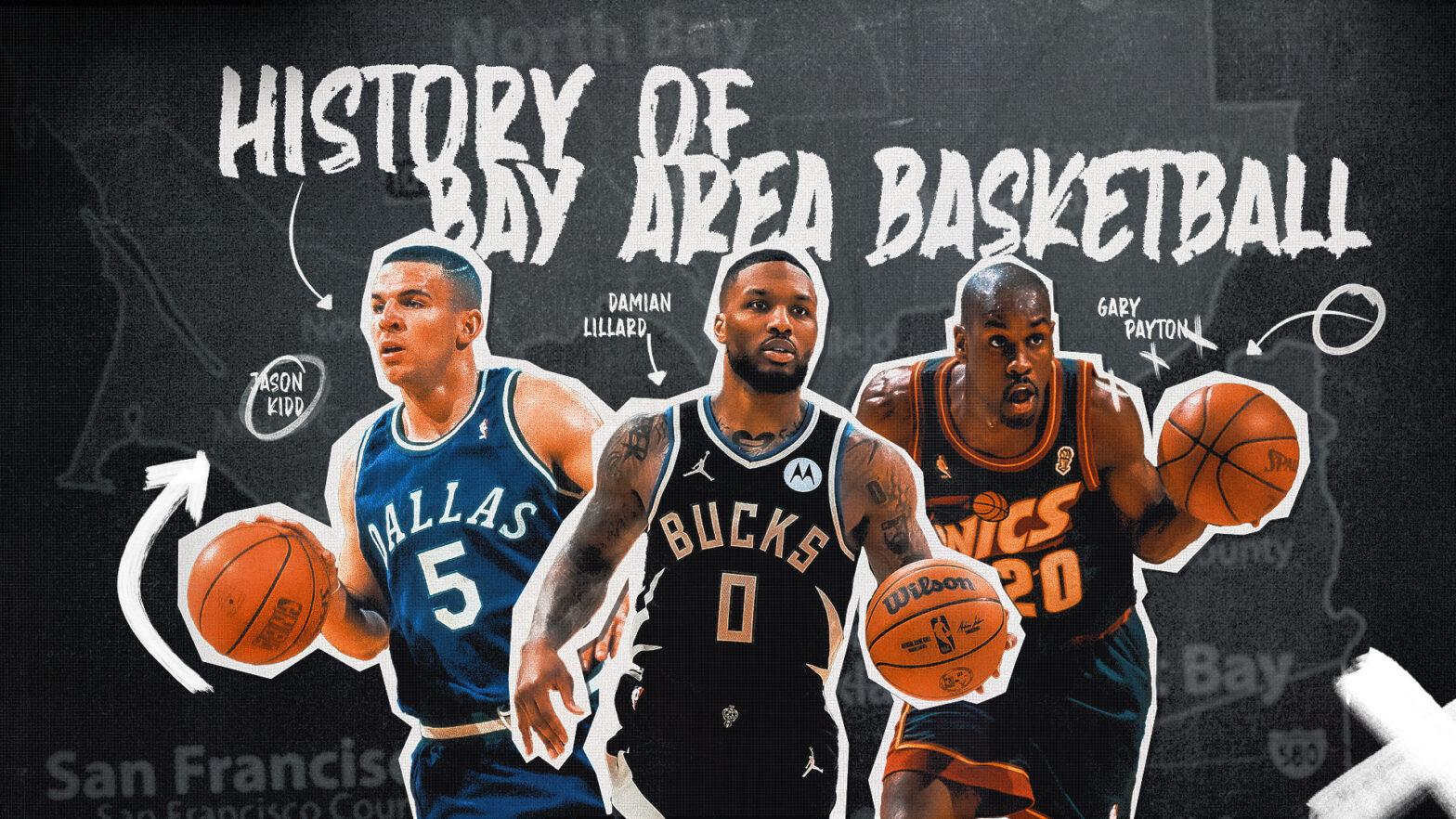

College of Alameda. Last fall this small community college welcomed a local superstar: Gary Payton. Yes, the Hall of Famer, NBA champion and man known as “The Glove” is the coach at Alameda. Payton wants the school to serve as a collegiate option for East Bay teenagers and also hopes to drop knowledge on a basketball program that has struggled as of late.

Berkeley High School. As the centerpiece public school in a town renowned for the arts, Berkeley High has a thick history of producing poets, musicians, actors, activists and teachers.

But in the ‘40s a skinny teen named Don Barksdale became one of the school’s most talented players. Problem: His coach cut him three straight years because the team already had its quota of Black players — one.

Barksdale eventually made the NBA and became a pioneer: he was the first Black player to be an All-Star, the first Black player to play on the U.S. Olympic team and be named All-America.

He was followed at Berkeley by Phil Chenier, a smooth guard who helped the Washington Bullets win their only championship.

Bishop O’Dowd High School. Brian Shaw was part of the new-blood basketball talent in the 1980s and ‘90s who competed on the local playgrounds, yet he bypassed the public schools in favor of Bishop O’Dowd, where he became, not surprisingly, the school’s finest talent. Shaw had a fine NBA career, was coach of the Denver Nuggets from 2013-15 and is an assistant coach on the LA Clippers.

When Shaw’s parents and sister died in a tragic car accident early in his NBA career, hundreds packed an Oakland church for the funeral. In attendance were all of the NBA notables from Oakland — Payton and Jason Kidd among them — in a show of unity and support.

Encinal Jr. Sr. High School (Alameda). Oakland’s best pipeline for baseball — Willie Stargell, Jimmy Rollins and Dontrelle Willis attended — became a basketball hotbed once Isaiah Rider emerged as the city’s best pure talent.

Rider went a step further as a junior and senior and was recognized among the state’s best hoopers. His game was undisciplined but energizing and Encinal played to sellout crowds, expecting (and getting) a show.

Rider became better known by his nickname, JR, once he made the NBA. And in a salute to his roots, he executed what he called “The East Bay Funk Dunk” to capture the 1994 dunk contest.

McClymonds High School (Oakland). In its prime of the 1950s and ‘60s, this East Oakland school flooded the NCAA and professional ranks of all sports with talent, just as those ranks became more accepting of black athletes. And the trend largely began with Russell.

He and his father escaped racism in Louisiana and upon arriving in Oakland, Russell discovered basketball. The rest is history. Raw at first, he soon showed the skills that made him an icon.

But look who followed his footsteps: Paul Silas and Antonio Davis, along with baseball’s Frank Robinson and Curt Flood, Jim Hines (Olympic sprinter) and someone who, after school, was discovered dancing in the parking lot before A’s games. He became MC Hammer.

McClymonds has since suffered from athlete exodus, like so many public high schools that lose promising hoopers to private schools and basketball academies. But its place in Bay Area history remains intact.

Oakland High School. Never being considered a consistent local basketball powerhouse helped this school, the oldest in the city, when it came time for Damian Lillard to find a public school where he could get playing time.

That was no problem at Oakland High. Even though Lillard wasn’t a nationally-ranked recruit, he helped the school go 23-9 as a senior and averaged 22 points per game.

A postscript: Oakland went 26-8 in 2023 and finally won its first boys’ state basketball championship.

St. Joseph’s Notre Dame (Alameda). When it came time to attend high school, Jason Kidd was already Oakland’s best teenager. Yes, he was that good in middle school after years of playing against older kids on the AAU level.

This means St. Joseph’s hit the jackpot when Kidd chose the private school route. He delivered a pair of state championships, was named the nation’s top prep player as a senior, was voted Mr. Basketball in California two straight years and collected other hoop honors.

Back in the early ‘90s, high school mixtapes were rare, yet somehow video of J-Kidd throwing bounce passes and lobs and no-looks managed to find their way to the mainstream anyway. He led an Oakland prep basketball renaissance that reopened a pipeline to the NBA.

Santa Clara College. Steve Nash was a hit once he arrived as a relative unknown from Canada. He led the Broncos to three NCAA tourney appearances and helped upset No. 2 Arizona. Speaking of two — that’s how many MVPs he earned in the NBA.

University Of San Francisco. When Russell stepped on campus, the Dons instantly stepped into prominence. Assisted by KC Jones, who later would join him in Boston, Russell steered USF to national titles in 1955 and ’56. The school also produced Pete Newell, a long-time hoop coach and teacher whose ideas impacted the game, and Bulls center Bill Cartwright.

Skyline High School (Oakland). The gym was packed to the ceiling in the mid-‘80s when Payton emerged as one of the city’s greatest — and loudest — talents. Along with Greg Foster, who also made the NBA, Skyline was a force and its games were must-watch, winning two straight city titles.

Payton was coached in AAU by his father, nicknamed “Mr. Mean,” who enhanced his son’s game — without curbing the trash-talking.

Stanford University. Imagine having not one set of twins make the NBA, but two? Stanford has that distinction with Jason and Jarron Collins, followed by Brook and also Robin Lopez who, by all accounts, didn’t assault the Stanford Tree mascot.

Pickup games from sunup to sundown

Brookfield Park (Oakland). When he was seven years old and snuck out of his home, Lillard could be found at Brookfield Park, where he soon had no problem getting chosen for shirts vs. skins. As part of the Ira Jinkins Recreation Center, Brookfield was one of the places to earn your stripes, one bucket at a time.

Lillard became so connected to the park that he essentially adopted it by holding annual community picnics, bringing together adults and children, once he cracked the NBA. Burgers, hot dogs, even horse rides, everything was on “Dame Dolla’s” dime. Brookfield and Lillard have been featured in commercials, and he name-drops it whenever possible. Maybe they might rename the park after him someday?

East Oakland Youth Development Center. One of the most important sites in Oakland, the EOYDC is a safe space for hundreds of thousands of youths who are enhanced by many programs, including basketball. The degree of mentorship and instruction is rich and helped the EOYDC become nationally recognized.

The Warriors, and especially Curry, adopted the center by making appearances and donating time and money. Nearly every Oakland kid with an NBA future — Kidd, Payton, etc. — passed through the doors, which opened in 1978.

Kezar Pavilion (San Francisco). At the southeast corner of Golden Gate Park lies the second-best place to hoop indoors in the city. The Pavilion hosts the San Francisco Pro-Am league every summer and attracts several NBA players and devotees looking for an offseason run.

Nearly all NBA players raised in the Bay have hooped inside the gym, along with several Warriors and even WNBA players. There’s no set structure: you show up, lace up, sign up and level up.

Mosswood Park (Oakland). The gritty grooming ground was an incubator for some all-time greats, starting with Russell, followed by just about everyone who made it out of Oakland and to the NBA. Mosswood was where you earned your reputation — or someone broke it. Mosswood was also where an Oakland playground legend named Hook Mitchell dunked over a car, long before Blake Griffin at the 2011 dunk contest.

Over time, the park fell onto hard times until the Warriors helped renovate it. Today, the Warriors’ logo is splashed on the jump circle, the backboards are fiberglass and once again the park searches for the next Kidd.

Oakland Convention Center. While folks went about their business at trade shows, banquets, meetings and whatnot, none knew that several floors up the Warriors held practice. Yes, a facility on the convention center rooftop served as the headquarters of an NBA team. It was a basketball oasis in the middle of a city and only locals knew about it.

Every so often, when the Warriors began winning titles, famous guests would stop by to watch practice. Like, it was a good day when Ice Cube paid a visit and messed around and got a triple-double.

When it was time to raise a toast

Lake Merritt (Oakland). The finish line of the Warriors’ parade route was conveniently located at the lake, not far from downtown and vast enough to accommodate large crowds. All of the speeches and the trophy raising happened at the lake, where Curry and Klay Thompson provided their final “splash” of the season.

Market Street (San Francisco). The main downtown strip was painted blue and yellow for the 2022 parade route. For the first time, a Warriors’ title produced a parade outside of Oakland, and The City was more than up to the task — Market Street annually hosts the Pride Parade, which attracts thousands.

* * *

Shaun Powell has covered the NBA for more than 25 years. You can e-mail him here, find his archive here and follow him on X.

The views on this page do not necessarily reflect the views of the NBA, its clubs or Warner Bros. Discovery.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.