Image credit:

(Photo by Eddie Kelly/ ProLook Photos)

The walk from one dugout to another is not far at Charles Schwab Field, just a few steps across foul territory.

But when Oregon State head coach Mitch Canham made that walk on Tuesday after his team’s season had just ended, it carried a gravity that transcended result or rivalry.

He approached the UCLA dugout quietly. The Bruins were still alive then, the last of the West Coast teams standing. Canham looked a few of their players in the eye and told them, simply: “Represent the West well.”

The Beavers had just fallen to Louisville. UCLA would fall next. And with Arizona’s exit already sealed, that moment now stands as the quiet coda to a summer of revival. A small, sincere gesture that underscored something deeper: The West Coast stood tall again. Not as champions, but as a force. Not as a conference, but as a collective. As an ode to the past.

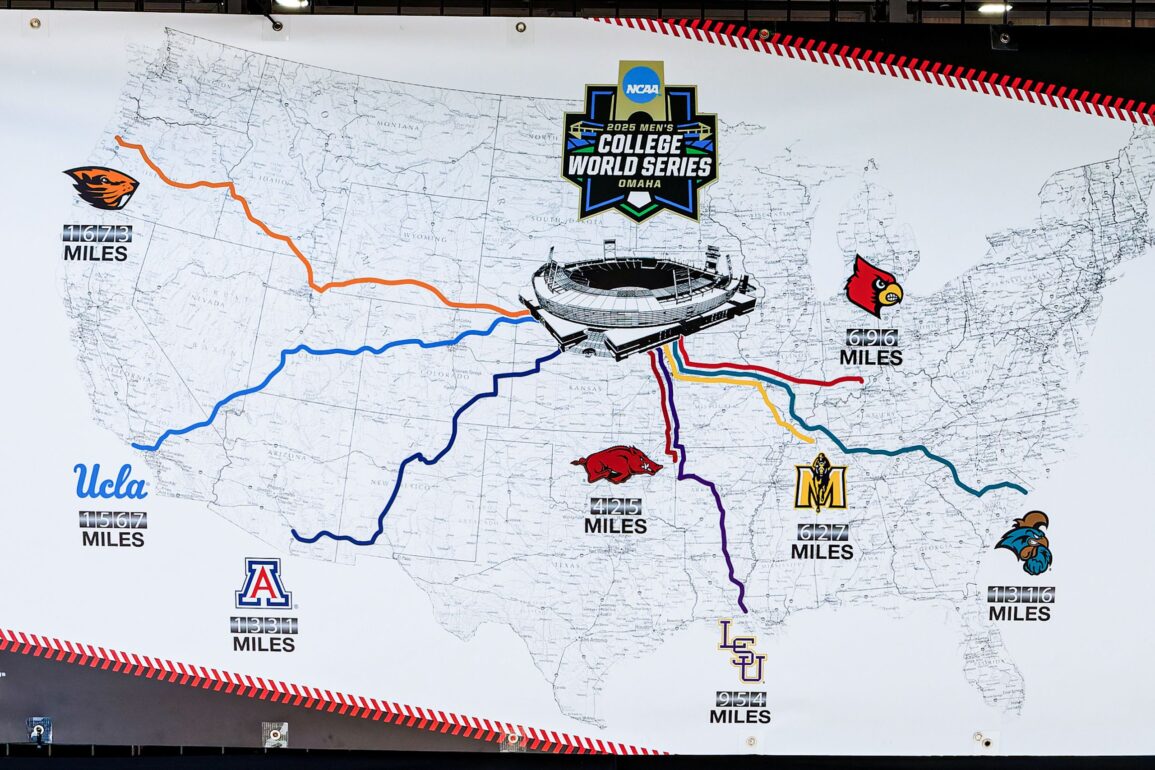

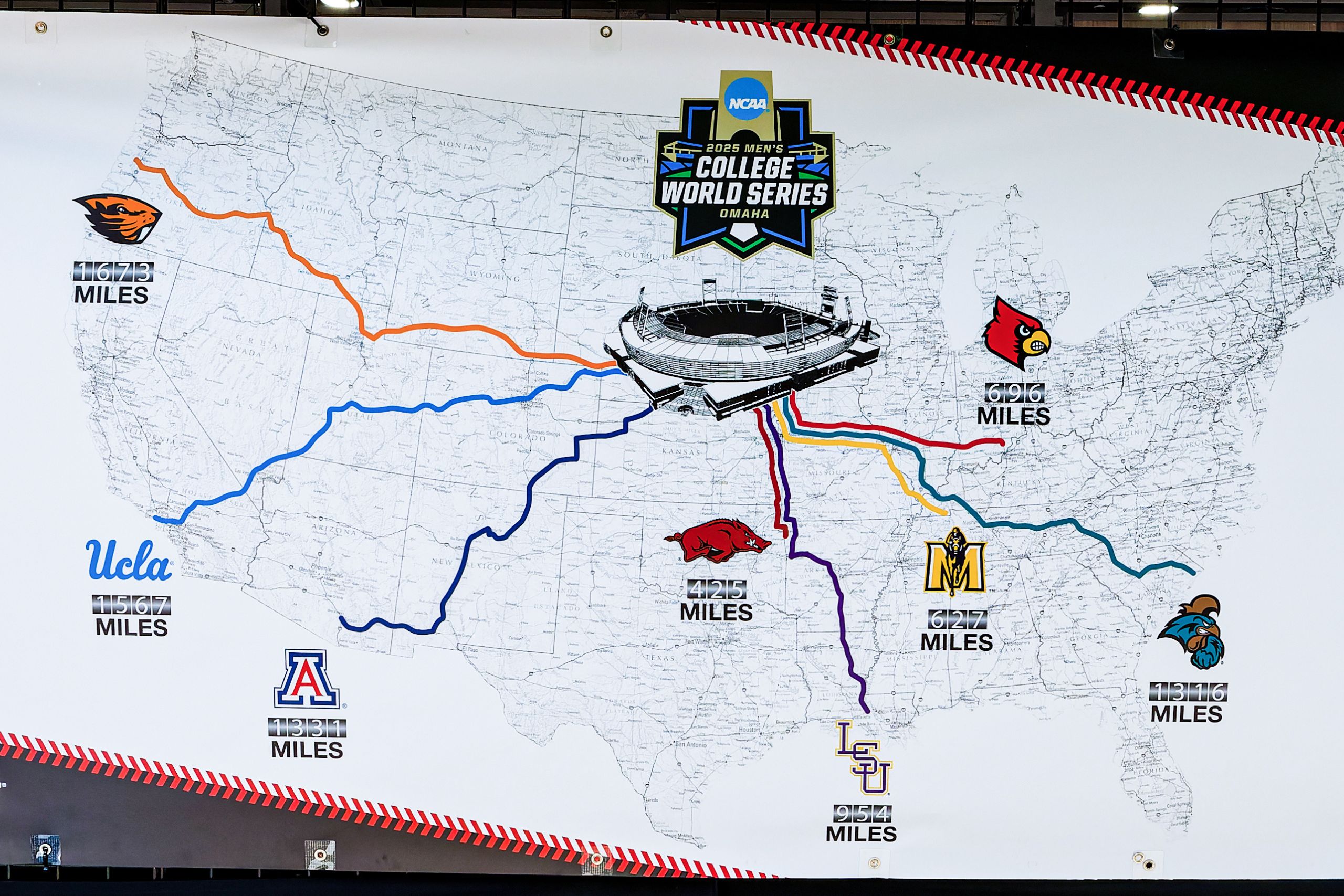

This West Coast trio played under different banners this spring—Big Ten, Big 12 and independent. They competed in different climates, adapted to foreign schedules and found new paths through the wreckage of what used to be the Pac-12. Somehow, despite it all, all three of them made it back to Omaha. UCLA, Arizona and Oregon State, together on college baseball’s biggest stage, marking what would have been the most representation for their former league since 1988.

They were not joined by the ghosts of a conference that once defined the sport. But they carried its legacy anyway.

This wasn’t just symbolism. It was success, tangible, earned and, in many ways, unexpected.

Arizona entered the field as a road-tested Big 12 tournament champion. Its ballpark kept its home run totals modest, but its bats exploded in the open air of Eugene and Chapel Hill.

“We have a team motto,” infielder Mason White said. “We call it the wear-down.”

Their path to Omaha was long, hot and brutal. They wore it like armor.

UCLA endured something more existential. The Bruins were displaced in the fall, removed from Jackie Robinson Stadium with no warning and forced to practice across Los Angeles while their home field sat in bureaucratic limbo. They bussed through traffic, lifted weights in makeshift clubhouses and somehow stitched together the kind of team that wins a Big Ten title in its first try a year after cobbling together just 19 total wins.

“We want to put our name back on the map,” said outfielder Dean West.

They did that and more.

Oregon State, meanwhile, had no league at all. The Beavers built their schedule with phone calls and faith, then embraced the road as if it were home.

“I think we’re more prepared than anybody to go do this thing,” OSU freshman Dax Whitney said before the College World Series.

The Beavers played with joy, purpose and a conviction that turned every delayed flight and meal-less layover into something greater.

“It’s all part of the plan,” Canham said. “We don’t shy away from what everybody perceives as difficult things.”

For a while, the West Coast looked like it might reclaim a piece of its former crown.

All three teams that reached super regionals advanced. Five West Coast programs are ranked inside the top 25 in RPI in mid June, the most since 2021. Seven different schools from the region reached the NCAA Tournament with at-large bids, and even teams like Cal—a program long forgotten in national conversations—knocked out Miami and Wake Forest in the ACC Tournament before falling short of a postseason bid.

There was no unified structure, no safety net of tradition to fall back on. Just talent, toughness and a belief—sometimes quiet, sometimes shouted—that the West Coast could still matter.

“We hear that all the time,” Arizona head coach Chip Hale said. “Obviously, recruiting is very difficult now. The SEC has been really strong in our areas. The only way we’re going to change this is to get back to Omaha.”

The question now, of course, is whether they can stay.

One magical summer cannot erase a decade of drift. Eight of the last 10 national champions have come from the SEC or ACC. The exceptions—Coastal Carolina and Oregon State—are rare outliers in a system increasingly built to consolidate power.

Facilities, television exposure and NIL dollars flow east. Talent does, too. Five current LSU players come from what used to be Pac-12 country, including four from California. The erosion isn’t theoretical. It’s already happened.

“There’s plenty of players,” Hale said. “You just have to get good players that are going to play good, solid baseball. And we’ve done that this year.”

But will they stay? Can the West hold them?

“Things have changed,” UCLA head coach John Savage said. “But I think we can build off this. There’s a lot of good players on the West, a lot of good coaches on the West. I think it has a bright future.”

That optimism isn’t naive—it’s earned. And if this season showed anything, it’s that belief still lives in places where others have stopped looking.

“You can win a national championship with players from Santa Barbara to San Diego,” Savage said. “They’re all over the place.”

This year, those players came together, not by geography, but by spirit. They boarded planes to Omaha, carried their region’s battered pride and tried to remind the sport what once made West Coast baseball so formidable—its depth, its development, its style, its soul.

That reminder came with no guarantees. The sun has set now. There are no West Coast teams left in the College World Series field. But there were three. And that matters.

They did not win a title. They may not win one next year. But this summer proved that the West still knows how to fight. How to unify. How to climb.

And when a West Coast team finally reaches the mountaintop again, when the walk across the field isn’t one of farewell but of celebration, it won’t be a revival anymore.

It’ll be a return.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.