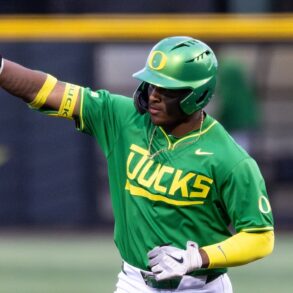

Image credit:

(Photo by Robin Alam/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images)

If you wandered the trade show floor at the American Baseball Coaches Association convention in Washington, D.C. this past January, it was impossible to miss the shift.

Technology booths sprawled across the space, packed wall-to-wall with screens, devices and demos. One stand measured batted-ball performance, another tracked arm force and fatigue. Around the corner, a startup promised real-time insights on UCL health thanks to a device that intricately measured grip strength. Across the aisle, another system proclaimed the ability to map a pitcher’s biomechanics down to the millisecond.

College baseball has fully entered its data age.

“I couldn’t imagine us really doing a full-on player development plan, executing our scouting reports and putting together our scouting reports without the data we have now,” said Jamie Tutko, LSU’s director of pitching development. “We’re literally using it every single day—games, practices, every single pitch.”

That level of integration wasn’t common even a few years ago.

As recently as 2017, when LSU was among the pilot programs to test TrackMan, even staffers weren’t sure what it was or how to use it.

“We were collecting all of the data not really knowing what it was about,” Tutko said. “And me being kind of an old-school type guy when I first got into working in baseball, I wasn’t totally against it, but I was like, ‘I don’t need this. I’ve got a radar gun. I can see with my own eyes.’”

But that skepticism didn’t last. Not for Tutko, and not for the vast majority of his peers.

By 2021, the shift was in full swing across the sport. The explosion of the NCAA transfer portal, the growth of private player development labs and the widening gap between resource-rich and resource-strapped programs accelerated the adoption of data-driven decision making.

“It really started to go wild,” Tutko said of LSU’s integration of data analytics. “We really started to be able to use it and understand it and use it correctly.”

The transition to analytics began around the same time at Wake Forest. Tom Walter, the long-time Demon Deacons coach, recalled the pivotal moment.

“We were one of the first schools to get TrackMan,” he said. “We had it for a year and didn’t use it very well or even understand what it meant, but I challenged our coaching staff. It was like, ‘Let’s become the experts at this.’”

For Wake, it wasn’t just about keeping pace. It was about finding an edge.

It used technology to dive into the pitching lab space, a way to develop arms in their own mold using fact-based feedback derived from an endless supply of numbers.

“I just feel like at Wake Forest, we’re never going to be able to line up and play the same game as some of these schools that have endless resources,” Walter said. “They have more scholarship dollars or better facilities or more resources in the NIL space. So we’ve got to find a competitive advantage.”

That edge evolved into a holistic system—analytics, biomechanics, pitch design, lineup optimization, defensive shifts, even recruiting models.

“We’ve built these systems for evaluating our current players, evaluating recruits, coming up with player development plans and everything in between,” Walter said.

Across the country, programs big and small have followed similar trajectories. At Arizona State, Jared Matheson, a 23-year-old pitching analytics coordinator, represents the sport’s new wave of young minds breaking in through data.

“The analytical side of baseball is on the up and coming,” Matheson said. “Some stuff you want to keep coach-facing, and some stuff you want to keep player-facing. Our guys are all in. They dove in head first and want to learn as much as possible.”

That duality—balancing deep data with digestible player insights—has become central to modern coaching. Where once scouting reports offered vague summaries—“this guy’s 86 to 88 with a slider”—they now detail pitch usage by count, movement profiles, hitter tendencies and much more.

“Now it’s like, ‘Hey, this guy throws 76% fastballs in this count and 36% in this count, and this is what his breaking ball looks like,’” Walter said. “There are no secrets anymore.”

The results are tangible: faster player improvement, more precise game-planning and more efficient recruiting.

But the revolution didn’t happen overnight. Most coaches trace its rapid acceleration to around 2018-19 as TrackMan’s data-sharing network grew. It got another boost a few years later as competitive pressures in the portal era mounted and player expectations evolved.

“There’s more teams in Division I baseball in the TrackMan sharing network than not,” Tutko said. “The amount of data that’s out there is crazy.”

The tools themselves are now ubiquitous—TrackMan, Edgertronic, K-Vest, Kinatrax, Hawkeye, Rapsodo, blast sensors, high-speed cameras and force plates. But as several coaches noted, simply owning the tools isn’t enough.

“It’s one thing to say that ‘Yeah, we have TrackMan’ … But it’s another thing to actually utilize it,” Tutko said. “And we feel like we’re utilizing it just as well as anybody else, if not better than anybody else in the country.”

For those who do, the gains are clear.

“The game is always evolving,” Matheson said. “If you can learn every aspect of data—whether it’s TrackMan or biomechanics—it kind of just puts another feather in your cap. It helps you build your resume and gives you an edge.”

– –

The first part of the equation is the ballpark’s dimensions: 314 feet down the line in right, 365 feet to right-center, 404 straightaway, 370 to left-center and 350 down the line in left.

Next comes the wind. On a neutral day in Athens, a ball struck just north of 90 mph at the proper launch angle will clear the right field wall. A firm line drive in the same direction is likely to find extra bases.

Left field is less forgiving. The prevailing wind blows in from that side, and with deeper dimensions, home runs that way or to center require real force and the right trajectory.

The final variables live inside each player. Air pull rates, average and peak exit velocities, swing planes—metrics that, through two years of refinement, Georgia’s staff has learned to weight and model against their park’s unique characteristics.

When Wes Johnson accepted the Bulldogs’ head coaching job, he understood the challenge in front of him. Georgia wasn’t a historical SEC power. It didn’t carry the built-in recruiting muscle as many of its conference foes.

If the Bulldogs were going to close that gap quickly, they had to be smarter.

“One of the things we worked a ton on, right when I got the job, I had worked really hard and put together a projection model that we used,” Johnson said. “You’ve got to trust the model. If you have enough data, you gotta trust it. That’s one of the things I learned in professional baseball.”

The park itself became a roadmap. Georgia’s staff began running extensive overlays—taking prospective hitters’ batted-ball profiles and mapping them into Foley Field’s layout under typical conditions. Who could play here, not just anywhere?

It was in that process that a name surfaced this past offseason: Robbie Burnett.

A lefthanded hitter out of UNC Asheville, Burnett wasn’t high on portal big boards. In fact, Johnson estimated only two or three schools showed any interest. And even those were lukewarm or came from a lower-major program.

But the Georgia model told a different story. Burnett’s pull tendencies, swing path and raw exit velocity suggested untapped power potential—especially to right field in Athens.

“When we put Robbie’s numbers in our ballpark, we’re like, ‘OK, Robbie can hit 20,’” Johnson said. “I told the staff Robbie will hit 20 for us.”

Burnett had the baseline metrics, and with adjustments, Johnson believed he could thrive.

“All I’ve got to teach this guy is to pull the ball a little more,” Johnson said. “And we’re gonna work on getting his exit velo as high as we can.”

It wasn’t a guess. It wasn’t a hunch. It was data refined into action.

“We’re moneyballing it, is what we’re doing,” Johnson said.

To say that it’s worked would be an understatement. In 53 games leading up to the NCAA Tournament, Burnett batted .318/.492/.732 with 20 home runs, 66 RBIs, 12 doubles and nearly as many walks (41) as strikeouts (48). Seventeen of his 20 homers have come in Athens.

“We knew exactly what we were getting,” Johnson said. “That’s how we’re building this — we want players who fit what this park gives us.”

Of course, such precision has limits. Building to your park means leaning into strengths at home, but it also requires adaptability on the road.

“When I tell people we recruit players to our ballpark, this is what I’m talking about,” Johnson said. “Now, it hurts when you go to Texas, and it’s a big ballpark, or Kentucky. Or the wind’s blowing in.”

That’s where versatility becomes currency. Positional flexibility—especially among hitters—has become a priority in Georgia’s model.

“When guys can play multiple positions, that moves the needle for us,” Johnson said.

What started as a workaround—an effort to compete with bigger brands—has quickly become identity.

“You gotta trust your model or you don’t,” Johnson said. “You’re playing the math.”

At Georgia, that math now drives swings, at-bats, and increasingly, roster decisions.

– –

For all the precision, for all the modeling, for all the numbers on screens and projections in staff meetings, one truth still holds: The game is played by human beings.

Wes Johnson will be the first to say it.

“You’ve got to trust your model,” he said. “But there’s still an art to it. You’ve got to have some gut in this game. You can’t just be a robot with it.”

That philosophy echoes across the programs now embracing data—not as a replacement for coaching instincts, but as a tool to sharpen them.

“You still have to recruit good baseball players,” said Tom Walter. “We can look at all the numbers we want, but there’s still an element of makeup, of toughness, of how a kid’s going to compete.”

At LSU, Jay Johnson sees it the same way.

“It’s a game being played by human beings,” he said. “There’s a character element to this. There’s a make-up element to this. There’s still an element of old-school scouting.”

What the best programs have learned is not to drown in the data. The right balance matters. The numbers can guide decisions—but they can’t play the game. They can’t recruit either, so teams are using the figures to identify talent but not to determine if each spreadsheet darling is truly the right fit.

“I’m never going to just blindly take a guy because his exit velocity is great,” Wes Johnson said. “If he can’t hit a breaking ball or if he can’t adjust, that doesn’t show up in one number.”

For players, too, there’s a learning curve. Some thrive on data-driven development, while others need simplicity. The staff’s job is knowing which is which.

“Our guys get all the information they need,” Walter said. “But we’re also careful about how much we give them. Sometimes less is more.”

That calibration—when to lean on data, when to trust the eyes, when to simplify—has become one of the modern coach’s most valuable skills.

“It validates a lot of things you’re saying for player improvement,” Jay Johnson said. “But it also gives them a pathway of how to get there. That’s where it really helps.”

At Georgia, that path is still being built. The program Wes Johnson inherited wasn’t one with a surplus of experienced arms or proven depth.

“I had three pitchers on the staff who had gone five innings in a college baseball game,” he said. “Only three.”

Data alone wasn’t going to solve that. It would take player development, culture and coaching—areas where Johnson has also invested considerable time, even if his model is fine tuned and producing.

“We can model it all day long,” he said, “but if we don’t make the players better, it doesn’t matter.”

At Wake Forest, even with one of the most advanced systems in college baseball, Walter still brings it back to the human element.

“We’re never going to have the finances to go out and get that high-end guy that everybody wants,” he said. “We’ve built our program on developing our guys. That’s what matters most.”

– –

For all the evolution still ahead, one consensus has already emerged: The data revolution isn’t slowing. If anything, it’s deepening—and changing the sport in ways that go far beyond pitch design and batted-ball profiles.

Wake Forest has even developed proprietary databases, housing pitch-level data across Power 4 baseball for the past seven years. Those insights don’t just shape who the Demon Deacons recruit. They inform how players are developed, how pitching plans are built, how games are managed—and increasingly, how coaching staffs operate.

“We’re looking for outliers,” Walter said. “Guys who do something unique. Then we take what makes them unique and build their plan around that.”

At LSU, the growth curve has been just as steep. Johnson likened the challenge to scouting in fast forward.

“There’s a profile you want,” he said. “There’s a blueprint of the player and the team. But it still comes back to: Can they take their talent and make it a usable skill at the highest level?”

For Johnson, the value of data lies in avoiding blind spots, especially as the recruiting landscape grows faster and more transactional.

“There’s a lot of safety in data and numbers,” he said. “It helps you predict the player better. You can still do your visual scouting. You can still trust what people you know are saying. But now you’re making even more informed decisions.”

Coaches still caution against leaning too far. The game, they remind, isn’t played on spreadsheets. But the tools will keep advancing. The models will get sharper.

And as those numbers keep climbing, one truth remains: In the game’s new data age, standing still is no longer an option.

“I think if you’re not doing it, you’re behind already,” Walter said. “And if you’re doing it and not evolving with it, you’ll be behind soon.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.