Let’s play a little game, Family Feud style.

The question: What do the New York Yankees do best?

We don’t need host Steve Harvey to shout, “The survey says!” to predict the results.

“Spending money” likely would be the No. 1 answer from rival fans.

“Making Hal Steinbrenner rich,” probably would be the top response from Yankees fans.

Advertisement

“Producing homegrown talent?”

That phrase probably would rank near the bottom with both groups, if it made the board at all.

Well, take a look at the 2025 Yankees. Look even beyond the incomparable Aaron Judge, whom the team retained as a $360 million free agent. Judge, as a player drafted or signed and developed by the organization, still meets the definition of homegrown.

The starting lineup frequently includes four other homegrown players — catcher Austin Wells, 25; shortstop Anthony Volpe, 23; left fielder Jasson Domínguez, 22; and one of two third basemen, Oswaldo Cabrera, 26, or Oswald Peraza, 24.

The rotation currently includes two homegrown pitchers, Clarke Schmidt, 29, and Will Warren, 25. And while the injured Luis Gil, 26, isn’t technically homegrown — the Yankees acquired the reigning AL Rookie of the Year from the Minnesota Twins — you could almost add him to the list.

Gil, a Dominican native who joined the Yankees before throwing a pitch in the U.S., is a player development success story. Ditto for one of the Yankees’ injured relievers, Jonathan Loáisiga, who originally signed with the San Francisco Giants, but like Gil joined the New York organization in rookie ball.

Of the Yankees’ current 26 players, eight are homegrown — and it was nine before they designated Yoendrys Gómez for assignment on Tuesday. That’s about 31 percent of the roster, the kind of percentage one might expect from a small-market team.

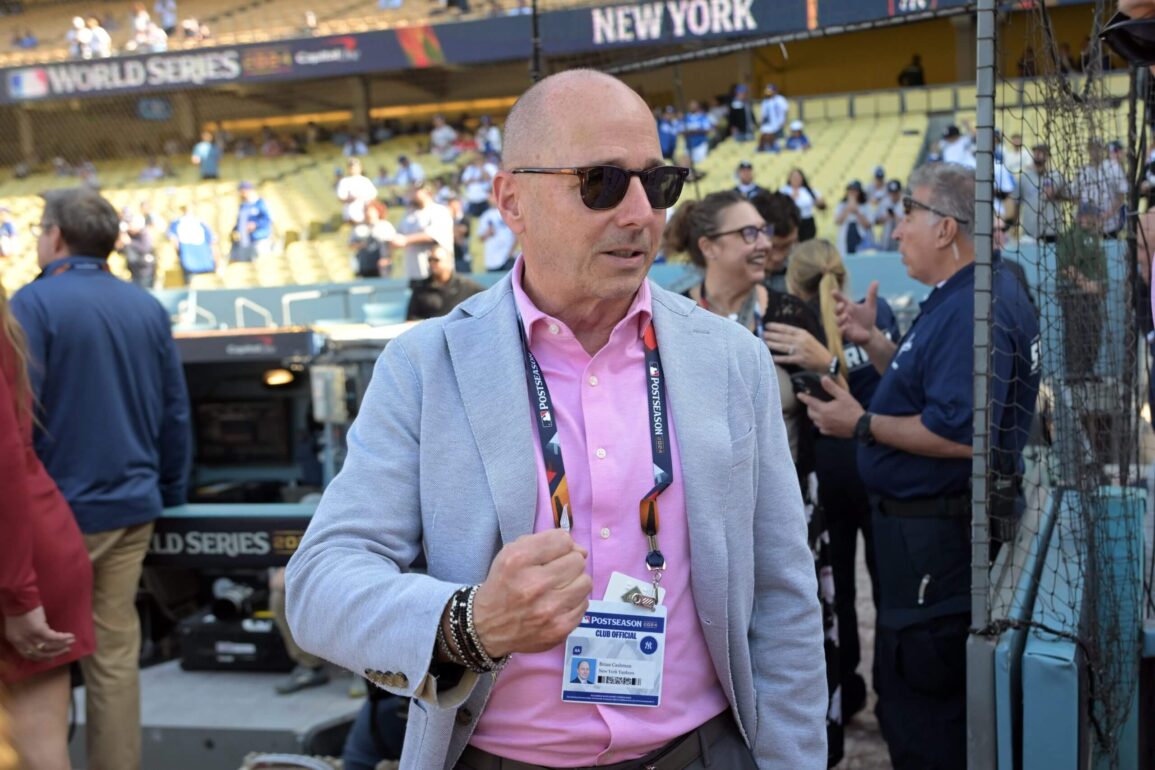

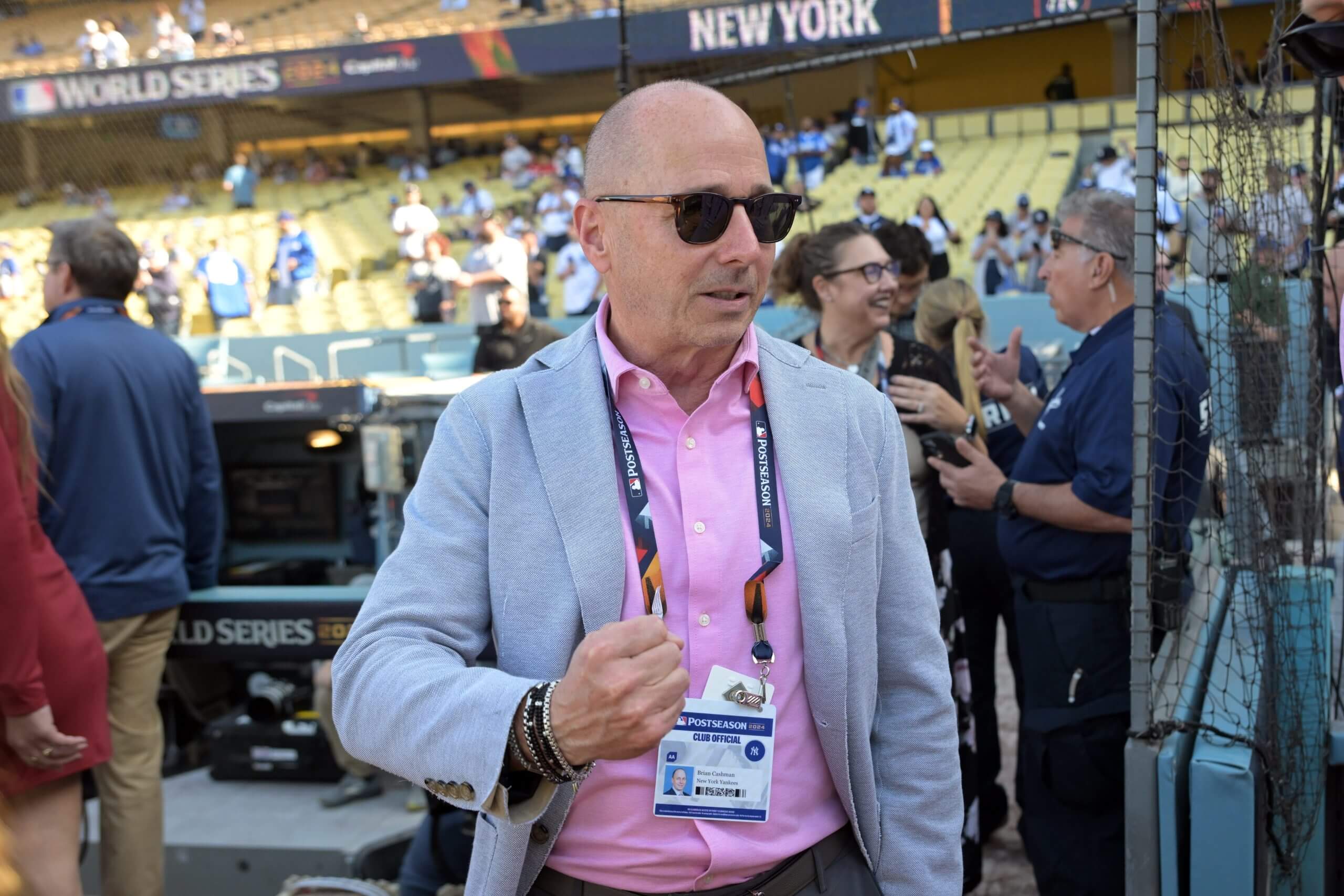

Brian Cashman’s 28-year tenure with the Yankees is the longest of any general manager in Major League Baseball. (Jayne Kamin-Oncea / Imagn Images)

“It’s a vital resource — you need to have success from your homegrown,” Yankees general manager Brian Cashman said. “Obviously, you can’t do it all by (exerting) the financial might we happen to have.”

A big-market club like the Yankees can better exploit that financial might by developing young, inexpensive talent. Such players help balance the payroll, creating opportunities to spend big at positions of need.

Advertisement

The Yankees’ current homegrown collection is not guaranteed to achieve lasting success. From the Baby Bombers of the mid-2010s, a celebrated group that included Gary Sánchez, Greg Bird, Miguel Andújar and Gleyber Torres (acquired in a trade), only Judge became a perennial star. A new foundation, though, certainly appears to be in place.

“At the end of the day, that’s what I feel my main job is — to provide some guys who can fill in and hopefully have a huge impact that allows a little greater flexibility for Hal and Cash to make moves at the top end,” Yankees farm director Kevin Reese said.

Now, before we get into the “what about” game — What about my team, Ken, look at all of our homegrown talent! — let’s get some things straight.

We’re excluding players who already were professionals in Asia — Yoshinobu Yamamoto, Roki Sasaki, Kodai Senga, Jung Hoo Lee, et al — and do not truly fit the definition of homegrown.

We’re also not arguing that the Yankees are the only team succeeding in promoting homegrown players to the majors.

The Baltimore Orioles’ core of young position players, led by Gunnar Henderson and Adley Rutschman, might be better than the Yankees’.

The New York Mets’ group, featuring the established Pete Alonso, Brandon Nimmo and Jeff McNeil, pitchers Tylor Megill and David Peterson and the latest wave headed by Mark Vientos and Francisco Alvarez, might be better overall.

The same arguably can be said of the Seattle Mariners, with Julio Rodríguez, Cal Raleigh and a dominant rotation that is almost entirely homegrown. And of the Atlanta Braves, from Ronald Acuña Jr. and Ozzie Albies, to Austin Riley and Michael Harris II, to Spencer Strider and Spencer Schwellenbach.

Other clubs — notably the Boston Red Sox, San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals — also belong in the conversation. The Los Angeles Dodgers might, too, if so many of their starting pitchers weren’t injured. And on many nights lately, the Los Angeles Angels’ lineup includes six homegrown players.

Advertisement

So, why focus on the Yankees?

Because they appear on the verge of producing their best homegrown group since the Core Four of Derek Jeter, Andy Pettitte, Jorge Posada and Mariano Rivera. Because they’ve evolved under Cashman, whose 28-year tenure is the longest of any GM. And because they face unique challenges: self-inflicted in some respects, but unique nonetheless.

The last time the Yankees drafted in the top 20 was in 2017, when they chose Schmidt at No. 16. In the seven drafts since then, the average position of their top pick was 25th. The average for the Braves was 19th, the Mets and Mariners 16th, the Orioles eighth.

Part of this stems from the Yankees’ success; they’ve missed the playoffs only five times during Cashman’s tenure. And part of it stems from their spending. Their top pick in 2024 dropped 10 spots, to No. 26, after they exceeded the first luxury tax threshold by more than $40 million. They will incur the same penalty in 2025, with their first pick falling to No. 39.

The Yankees compromised themselves in other ways as well. Three times in the past five years, they signed free agents (Gerrit Cole, Carlos Rodón, Max Fried) who rejected qualifying offers, at the cost of second- and fifth-round selections and $1 million in international bonus pool space. The fewer picks a team makes, the less it can spend on domestic amateurs. The Yankees’ draft bonus pools the past five years averaged in the bottom five.

No one should pity the Yankees for sacrifices that resulted from them flexing their financial muscle. They also whiffed with some of their first rounders in the past decade (Blake Rutherford, TJ Sikkema, Anthony Siegler), often compensating for those mistakes with lower-round finds. Their current homegrown group is all the more impressive, considering their low draft positions effectively force them to play from behind.

Aaron Judge, who is the Yankees’ most impressive homegrown player of the 21st century, was drafted 32nd out of Fresno State in 2013. (Cal Sport Media via Associated Press)

Virtually every team could have taken Judge, who was drafted 32nd; Volpe, who went 30th; or Wells, who went 28th. Warren was an eighth-round pick, Rice a 12th-rounder. And while Domínguez was a $5.1 million international signing, Peraza, Cabrera and Gómez were relative bargains, at $175,000, $100,000 and $50,000, respectively.

Advertisement

For all that, rarely is the Yankees’ farm system considered one of the best in the game. Earlier this year, The Athletic’s Keith Law rated it 21st, Baseball America 25th. Since 2020, the Yankees’ highest rank from BA was 10th, and its average was 16th. Law had them in his top 10 twice, but their average rank was 14th.

A major reason? Trades.

“When you’re competitive every single year, you’re trading prospects every single year,” Arizona Diamondbacks GM Mike Hazen said. “The Dodgers, the same thing. They continue to have a top-three farm system and they make trades at the deadline every year to trade away good players.

“For those teams that are in it every year, you’re not allowed to just stockpile young players. You have to keep the right ones and trade the ones who aren’t going to burn you necessarily, but can still get a trade done.”

Cashman does not always acquire the right players. His deals for Joey Gallo, Josh Donaldson and Frankie Montas are among his worst. Like every club, the Yankees occasionally get burned by players they trade, waive or lose in the Rule 5 draft. But what stands out most is the sheer number of homegrown players they’ve moved in recent years. Which is further evidence of their success in identifying and developing international and domestic amateurs.

Consider this partial list of relatively recent homegrown Yankees now with other teams (not all went directly to their current clubs):

Starting pitchers: Hayden Wesneski (Houston), Randy Vásquez (San Diego), Richard Fitts (Boston).

Relievers: Garrett Whitlock (Boston), Greg Weissert (Boston), Mitch Spence (Athletics), Trevor Stephan (Cleveland).

Catcher: Carlos Narváez (Boston), Agustín Ramirez (Miami)

Infielders: Josh Smith (Texas), Ezequiel Duran (Texas), Trey Sweeney (Detroit)

Outfielders: Brandon Lockridge (San Diego), Miguel Andújar (Athletics), Kevin Alcántara (top 100 prospect for the Chicago Cubs).

Advertisement

OK, not a group of All-Stars, though Smith, sacrificed in the Gallo trade, won the 2024 American League Silver Slugger in the utility role. But the list can be expanded to include other players who essentially began their careers with the Yankees.

Michael King (San Diego) and JP Sears (Athletics) are major-league starting pitchers the Yankees acquired when they were in A ball, developed and later traded. Catcher Gary Sánchez (Baltimore), catcher Kyle Higashioka (Texas), infielder Rob Refsnyder (Boston) and left-hander Nestor Cortes Jr. (Milwaukee) are 30-something players who also started in the Yankees’ system.

The Yankees’ trade with the San Diego Padres for outfielders Juan Soto and Trent Grisham in December 2023 was perhaps the best recent example of Cashman leveraging mostly homegrown young talent to make a major splash.

In the trade, the Yankees parted with King, a 2008 seventh rounder (Higashioka), a 2022 second rounder (pitcher Drew Thorpe) and two pitchers who cost a combined $45,000 in the international market (Vásquez and Jhony Brito). And when the Padres used Thorpe as the centerpiece of a subsequent deal for Dylan Cease, it made an outstanding trade for them even better.

Scanning the visiting clubhouse in Cleveland on Monday, Volpe spotted one former minor-league teammate after another.

“We all know each other well, and we’re all going at it with the same goal,” he said. “We’re up with the Yankees and we’re competing to be the best we can be. To have people you have stuff in common with is cool.

“You feel so comfortable. Even now. Talking about old stories, and having other guys being able to tell stories with you, our funny minor-league stories, guys who were with you.”

The value of the shared history cannot be measured. Neither can the value of a player’s makeup, a point of emphasis for the Yankees, according to the team’s amateur scouting director, Damon Oppenheimer.

Advertisement

The Yankees are one of the game’s most analytically inclined organizations. Their reliance on data occasionally is a flashpoint for those critical of Cashman. But Joe Torre’s famous warning to Cashman, as recounted in the book “The Yankee Years,” resonates in the organization, too: “Do yourself a favor, Brian, and never forget there’s a heartbeat in this game.”

“Our scouts have gotten to know these players. They know their makeup,” Oppenheimer said. “I think that’s the big separator. In some places, it’s just not as important.”

Oppenheimer and Reese are quick to credit the Yankees’ homegrown players who reached the majors, for their talent, their willingness to be coached, their burning desire to improve. But Reese also cites the integration, spearheaded by Cashman, of the team’s wide-ranging departments, from player development to amateur, international and professional scouting, analytics to performance science to strength and conditioning,

“As we’ve evolved as an operation, we had to break down the walls that were separating them,” Cashman said. “They all had to be linked. They all had to be communicating.”

As the Information Age continues, providing increasingly more data, it’s critical for organizations to achieve such cohesion. The tools of evaluation keep changing. An outfielder with the Yankees in 2005-06, Reese said instruction was much more informal.

“There certainly was a little bit more of, ‘Hey, just go out there and put up numbers and make small micro-adjustments on the fly,’” Reese said. “It was a little more on a whim than the decisions we now make.”

Today?

“The advice comes from a ton of different people,” Reese said. “It’s not only the on-field coaches. It’s the coordinator groups that lead those individual departments. It’s the analysts who notice something behind the scenes and might recommend an adjustment.

Advertisement

“Outsiders probably have an idea that an organization is a group of people, but every time something good or bad happens, there’s always one person or one coach who gets the credit or blame. I don’t think anybody knows just how many people are involved in these decisions, not only to acquire players, but to make adjustments, to make recommendations to players and to convince them this is why we want to make said adjustment.”

All 30 clubs strive to develop such synergy. Some just do it better than others. Which isn’t to say the Yankees, or any other club, have everything figured out. As the Yankees’ experience with the Baby Bombers demonstrated, things do not always turn out as expected.

Judge is Judge. Wells looks like a star, and another player development win; few in the game thought he would be a passable defender at catcher. But Volpe might never hit. Domínguez might never fulfill the otherworldly hype he generated as an international prospect. Rice might never be more than the next Greg Bird or Kevin Maas.

The Yankees, though, can at least say they’re producing homegrown talent. And at the moment, it’s serving them rather well.

— The Athletic’s Brendan Kuty contributed to this story.

(Top photo of Domínguez, Rice and Volpe: Mike Carlson / MLB Photos via Getty Images)

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.