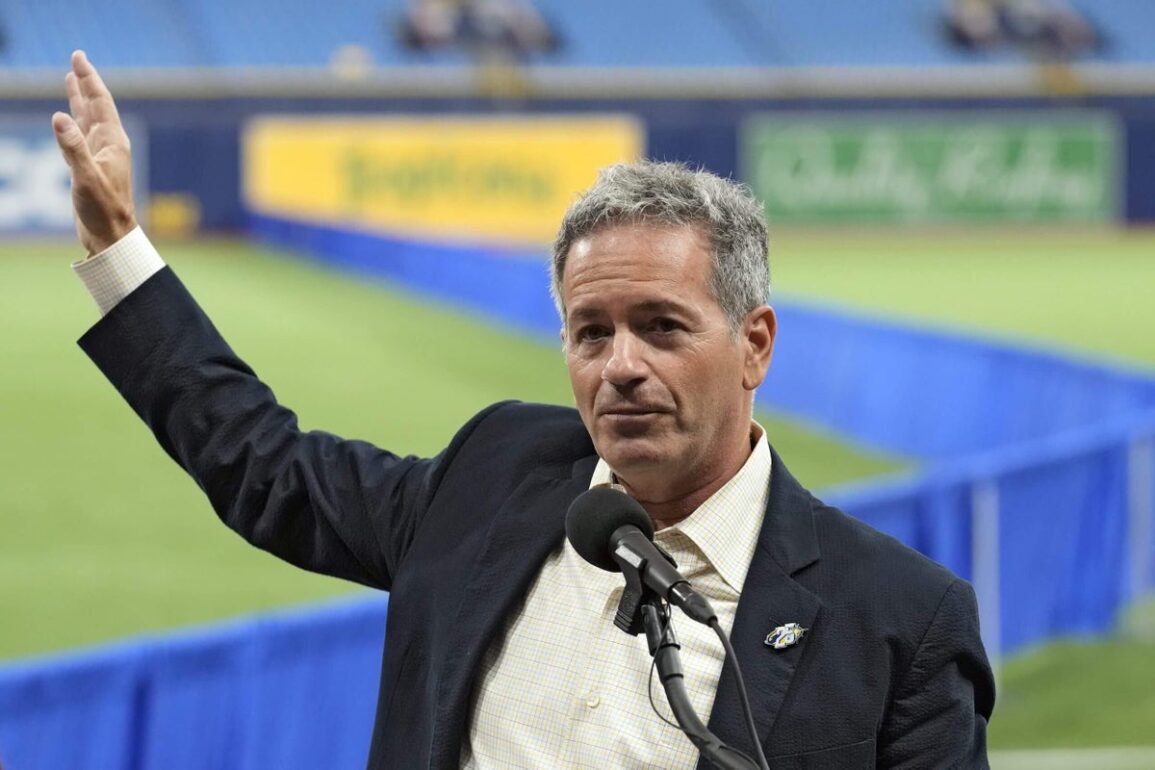

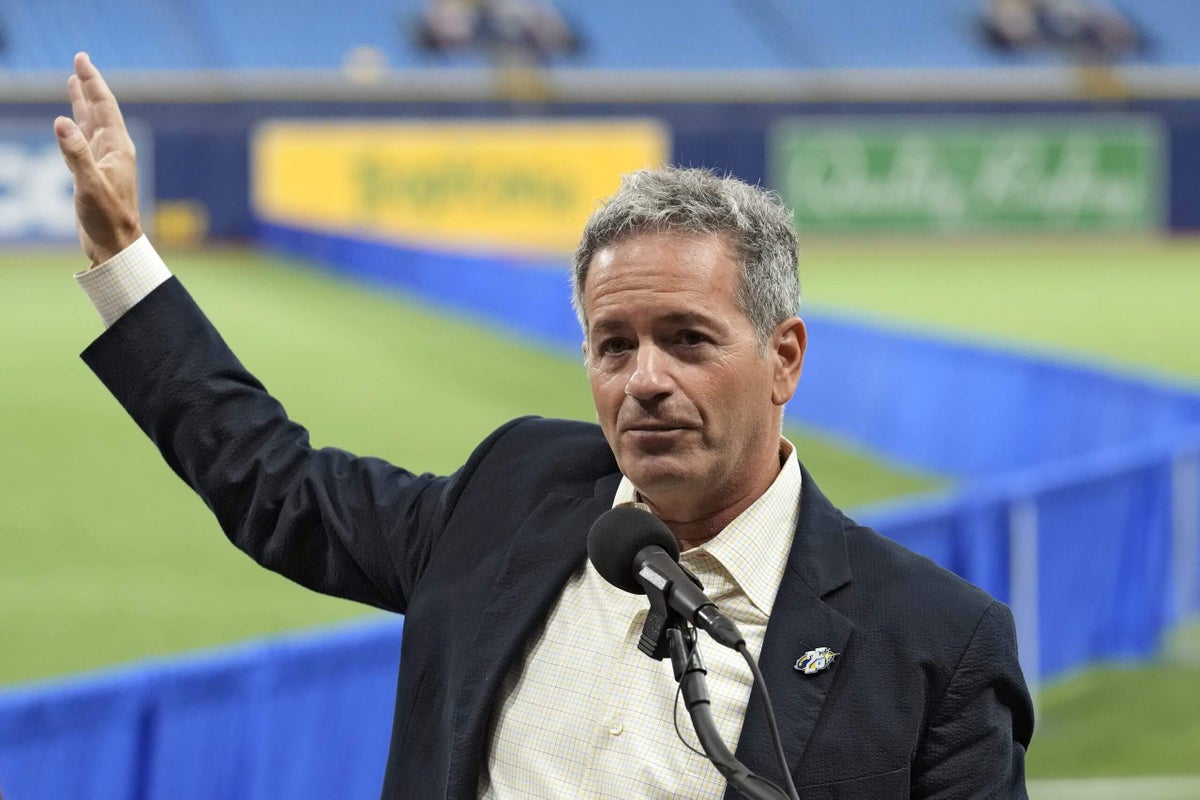

As he considers walking away from a stadium deal in St. Petersburg, Fla., Tampa Bay Rays owner Stu Sternberg is being pressured to sell his team by commissioner Rob Manfred and some other owners, people briefed on the ownership-level conversations who were not authorized to speak publicly told The Athletic.

Advertisement

One includes the family of Edward DeBartolo Jr., which has roots in Tampa, three people briefed on the discussions said. Members of the DeBartolo family own the San Francisco 49ers, although Edward Jr. is no longer involved with that team. Former New York Yankees minority owner Joe Molloy is involved in the DeBartolo effort as well, but does not carry the same financial weight as DeBartolo.

The people briefed on the team’s discussions also said Tampa businessman Dan Doyle Jr., who reportedly pulled out of a previous process to buy the Rays in 2023, is part of another group with recent interest.

MLB and the 49ers declined comment. Doyle and Molloy could not immediately be reached for comment.

“I’m interested to read about what industry partners have told you about our franchise and its future,” Sternberg said when reached for comment Sunday.

Sternberg has also been courting minority investors. If the team is sold, MLB ultimately wants the franchise to remain in Florida, with an eye on the Ybor City neighborhood near downtown Tampa if St. Petersburg does not work out. People briefed on the process pointed to Orlando as a possibility as well.

But after 17 years of trying to find a new stadium, Sternberg appears to be on the clock to firm up a long-term plan, be it by selling or building. If he doesn’t, he risks MLB trying to take away at least some of the team’s revenue-sharing money in the future, people briefed on the ownership-level conversations said. The Rays receive around $60 million from that pool, people briefed on the team’s finances said.

Two key dates loom. The first is March 31, a deadline for Sternberg to meet several obligations that would push forward a $1.3 billion stadium deal in St. Pete. The Rays have been telegraphing that they are unlikely to meet those obligations, however, which would leave them on square one, or close to it: in search of a municipality in Florida that will agree to publicly fund some of a ballpark.

Advertisement

The Rays planned to contribute $700 million to the stadium in St. Pete. But the team is arguing that a delayed county vote led to a holdup in construction and therefore, increased costs. They do not believe they should cover those costs on their own.

The delayed vote came on the heels of hurricanes in the area last fall, including Hurricane Milton, which ripped up the roof of the Rays’ home, Tropicana Field. Because of the damage to Tropicana, the Rays this year have to play at the New York Yankees’ minor-league complex, and might have to go there again in 2026 as well.

Chris Latvala, a commissioner in Florida’s Pinellas County who has been a vocal critic of Sternberg, believes a sale is coming.

“If Stu walks away from this deal, I think the owners and Major League Baseball will see that he either has an unwillingness to do a new stadium in Tampa Bay, or he has a financial issue that prevents him from doing a new stadium in Tampa Bay and there needs to be an ownership change,” Latvala said. “I do believe that we’ll have new ownership with the Rays at some point in the near future.”

Team president Matt Silverman said Sternberg’s access to the money is not the issue, however.

“It’s not a question of whether we have the funds. We do,” Silverman said. “The question is whether it’s a good use of those funds to commit us and MLB to this ballpark for the next 30 years.”

A more powerful deadline, however, might loom at the end of 2026, during collective bargaining between MLB and the players’ union. MLB and the Major League Baseball Players Association could, at that time, agree to ways to lessen the team’s share in revenue sharing or put contingencies around it.

The Rays, however, believe they should not be committing to a stadium project where they don’t think they can thrive, people briefed on the possibility of the team’s sale said. The Rays feel that fellow club owners should be glad the team does not want to sign up for 30 more years of middling success — because it would mean they’d still be propped up by revenue sharing. The team also feels singled out compared to other smaller-market teams that have been less successful on the field, including in comparison to the Miami Marlins.

Advertisement

But if Sternberg walks away from the deal in St. Pete at the end of the month, it might be difficult to revive.

“I don’t know what there would be left to negotiate,” Latvala said. “We have a deal, and it’s on the table. I’m certainly not going to give them more money, so I don’t really know what’s left to negotiate with them.”

Construction in Tampa might only be more expensive, which could make it hard for the team to pivot there while he remains the owner. New investors in the team could change that dynamic, but it’s unclear how Tampa politicians would receive Sternberg after this episode in St. Pete.

Levers of power

Next offseason, Manfred can exert some financial pressure on the Rays if he decides to lessen or eliminate their payments from two pots of money he controls: the commissioner’s discretionary fund and the commissioner’s supplemental discretionary fund. The league does not publicize those distributions, but the Rays have been a beneficiary, people briefed on that process said. Those payments are typically not huge — several million, rather than tens of millions, but they’re not negligible either.

The most powerful lever MLB has over the Rays, though, likely lies in the CBA. When it expires in December 2026, Manfred is poised to try to overhaul the sport’s revenue-sharing system, and that might leave the Rays with less of other teams’ money coming to them.

Now, the players might rebuff large-scale change. Either way, the league and the union could agree to a special carve-out for the Rays that would limit their revenue-sharing funds if they do not get a new stadium deal in place by a certain date.

In the current CBA, which covers 2022-26, the sides agreed to a provision that would have taken away revenue sharing from the Athletics had they not reached a binding stadium agreement by, Jan. 15, 2024. The team met that deadline.

Advertisement

The A’s were a different case than the Rays, however. Oakland’s market size typically would preclude a team there from getting revenue sharing at all. But the A’s had a special allowance to receive it, and the Jan. 15, 2024 deadline served as an expiration date. In St. Pete, the Rays normally would receive money. But that doesn’t mean MLB and the MLBPA couldn’t tie their slice of the pie to a new stadium.

In the big picture, the Rays find themselves staring down not only their local government, but also the league office and the sport’s other owners.

What’s the rush?

The Rays could probably sell for a higher dollar value were potential buyers allowed to relocate the team. But MLB does not want the Rays to move out of the overall market, believing it still viable. Nor does the league want to give up a potential expansion city like Nashville or Portland, Ore., or Salt Lake City. Whether to allow relocation is ultimately up to MLB and the other owners, not Sternberg.

So with discussions not yet meeting Sternberg’s target price, he doesn’t appear to have had a great incentive to act quickly. Revenue sharing and the team’s balance sheet today might be more appealing than reducing his asking price or taking on the expense of new construction in St. Pete.

But Manfred and other owners appear out of patience. Sternberg a few years ago pushed a plan for the team to split the season between two countries: in the U.S. in Florida, and in Montreal in Canada, which Manfred eventually nixed.

Today, large-market clubs that pay the most into revenue sharing are not happy, and at least some of the small-market teams are annoyed too.

“You’re San Diego, you’re Milwaukee, you work your a– off,” said one person briefed on the ownership-level discussions.

To an extent, the Rays are keeping the owners from the windfall of an expansion fee.

Advertisement

Manfred wants the league to have chosen two cities for new teams before his planned retirement in 2029, but he has also long said that the process would wait until the Rays’ situation is solved. The Rays aren’t definitively the only hold-up, though. Some owners might be hesitant to expand until the A’s are settled in Las Vegas or the league has a plan for the Miami Marlins, who are struggling to draw.

Forbes estimates the Rays to be worth $1.25 billion. Sternberg bought the team for $200 million in 2004.

DeBartolo Jr. oversaw the 49ers’ five-time Super Bowl-winning dynasty. He also received a presidential pardon from President Donald Trump following his involvement in the corruption case of former Louisiana governor Edwin Edwards. After DeBartolo Jr. was indicted for failing to report an extortion attempt by the former Louisiana governor, the NFL suspended him for one year and he later ceded control of the 49ers to his sister, Denise DeBartolo York, in 2000.

Molloy ran the New York Yankees when George Steinbrenner was suspended in the early 1990s. He was previously married to the daughter of the late Yankees owner, and had reported interest in buying the Marlins in 2017.

Doyle Jr. and his father started the office technology company DEX Imaging in 2002. They sold it to Staples in 2019 before buying it back in 2024.

(Top photo of Sternberg: Chris O’Meara / Associated Press)

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.