Welcome to Sliders, a weekly in-season MLB column that focuses on both the timely and timeless elements of baseball.

When Rhys Hoskins joined the Milwaukee Brewers before last season, manager Pat Murphy gave him a new nickname: Pee Wee. The Brewers list Hoskins at 6-foot-4 and 241 pounds, but his first name sounds like “Reese,” like the Hall of Fame shortstop Pee Wee Reese … get it?

Advertisement

Yeah. It didn’t stick.

“That’s kind of fallen by the wayside this year,” Hoskins said by phone on Thursday. “It’s mostly just been Rhys, which is maybe a little boring.”

For the Brewers and Hoskins, there’s no need to force it anymore, physically or verbally. Boring is beautiful.

In his last 33 games before Thursday, when Milwaukee opened a four-game series in Pittsburgh, Hoskins was hitting .349 with seven home runs and 23 runs batted in. His average and on-base percentage ranked second in the National League in that span, and his 1.057 OPS ranked third.

If he keeps it up, Hoskins could make an All-Star team for the first time in his eight-year career. His power has been essential for a Brewers team that ranked 28th in the majors in slugging percentage through Wednesday, at .349.

“He’s healthy, his attitude and his mindset are terrific and he’s a great leader around a very, very young position player group,” Murphy said. “He understands what they’ve been through, he speaks up, he’s very courteous but stern. He definitely is a pillar on this team for sure.”

Hoskins, 32, spent 10 seasons in the Philadelphia Phillies’ organization, reaching a high and low point in succession: a surprise World Series appearance in 2022, then a season-ending injury (torn left anterior cruciate ligament) the next spring.

Bryce Harper learned to play first base in Hoskins’ absence, effectively ending his tenure in Philadelphia. The Brewers play there next Friday and Hoskins will likely be greeted warmly, as he was last season, when he stole a base in his first game back.

Hoskins beat a throw from J.T. Realmuto, the Phillies’ strong-armed catcher, then smiled at his old friend from second base. It was by far the most fun of his 20 career steals.

“Yeah,” Hoskins said. “Always will be.”

Hoskins also homered in that game, one of 26 for the season, trailing only the departed Willy Adames in a division-winning lineup. But Hoskins’ rate stats were all career lows (.214/.303/.419), and he declined to opt out of his two-year, $34 million contract. A sturdier follow-up season, he believed, could only be more productive.

Advertisement

“I learned that a year’s a long time, especially in the baseball world,” Hoskins said. “Not that there was divided attention, by any means, but there’s so much energy spent on trying to make sure the body felt right or normal, whatever normal was going to be. Coming back from the injury, even if it was just unconsciously, I’m sure I wasn’t moving the way I was used to and that leads to compensation within the swing.

“We’re really good at compensating, but that often leads to issues that you don’t even know are happening. And if I can look back now, that’s probably the road that I found myself on. We’re doing all we can to compete during the year and deal with what we’ve got. But after a pretty normal offseason for me, I got a chance to be a full baseball player again instead of being a rehabber and that’s made a huge difference.”

Hoskins also made an important mechanical change after starting slowly this season. Hitting coach Al LeBoeuf explained that Hoskins now strides earlier, so his front foot lands before the pitcher delivers the ball. That allows Hoskins to wait a beat longer for his pitch and move more efficiently when he gets it.

“There’s no risk whatsoever,” LeBoeuf said. “He’s not sacrificing power or speed, but he’s gaining the most important thing in the ability to command the strike zone. Because you’re only as good as the pitches you swing at.”

That has been the foundation of Hoskins’ surge. According to Fangraphs, he was chasing just 19.5 percent of pitches outside of the strike zone through Wednesday, tied for ninth lowest among 164 MLB hitters.

It is also Hoskins’ lowest rate since 2018, his first full season. Selectivity has improved his outlook.

“I feel like a tough out up there, which is always a good place to be as a hitter,” Hoskins said. “I’m making pitchers beat me in the zone maybe better than I ever have, or at least comparable to some of the other nice little runs I’ve been on.

Advertisement

“Making guys beat me in the zone gets me into better counts. And whether that’s leading to better aggression in those good counts or just taking my walks, I’m up there trying to not make outs and pass the baton to the next guy.”

The chain reaction unfolds from there, Hoskins said: better approach, better results, better mentality.

“Consistent results lead to confidence,” he said, “and when you walk up there with confidence, you’re a much more dangerous hitter.”

Joe Garagiola’s notebook goes to Cooperstown

The Arizona Diamondbacks had gone more than 4,000 games since their last defeat while scoring 11 or more runs. Then, this season, it happened three times in a month. As a wise old catcher once said, “Baseball is a funny game.”

That was the title of a book in 1960 by Joe Garagiola, a former player then embarking on a new career as a humorist, television host and Hall of Fame broadcaster. The book was a best-seller, but another one, never published, defined Garagiola best.

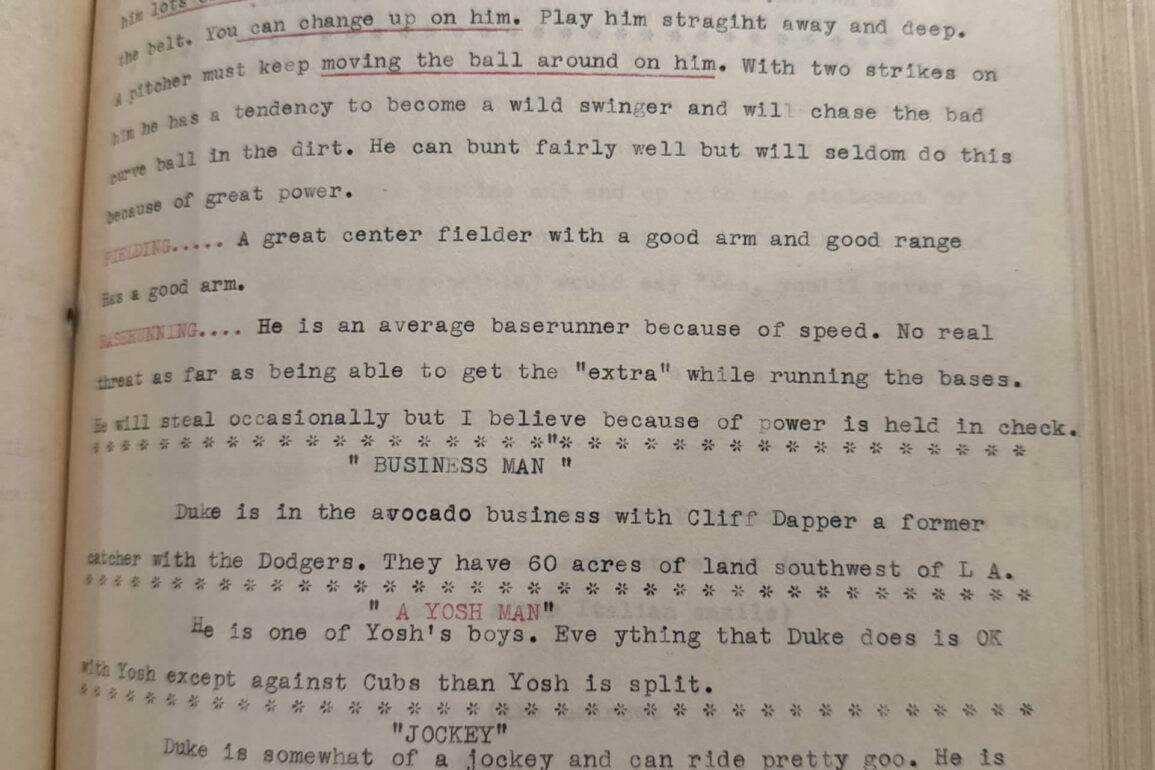

Garagiola’s grandson, Chris, 33, is now the Diamondbacks’ radio play-by-play man. For years, he held onto his grandfather’s press-box companion: an unmarked notebook with a green canvas cover, brown leather corners and around 200 pages of typewritten scouting reports and anecdotes he used while calling games for the St. Louis Cardinals and NBC in the 1950s and ’60s.

“When your loved ones pass, there are only so many ways you can connect with them in a meaningful way,” Garagiola said of his grandfather, who died in 2016. “And that book — more than a picture, more than an autograph — this was him.

“You’ve got to understand, I got serious about broadcasting after he died. There was no advice, he never got to listen to me (call a game). So any questions that I had about broadcasting — how to frame this, how to prepare for a certain player – this book was the closest to an answer that I was going to find.”

Joe Garagiola’s scouting report on future Hall of Famer Duke Snider. (Courtesy of Chris Garagiola)

For years, people have told Garagiola how much they enjoyed his grandfather’s work, especially on NBC in the 1970s and ’80s. Yet few people under 45 have much memory of “The Game of the Week,” and to preserve his grandfather’s collected wisdom, Garagiola thought the time was right to part with the book.

Advertisement

He passed it on to the Hall of Fame in spring training when Josh Rawitch, the Hall’s president, visited camps in Arizona.

“This is probably the last chapter of people being like, ‘Oh, Joe Garagiola, I loved him,’” he said. “We all fade with time, right? But at least that will be there and it will have stories about some of the all-time greats.”

The stories are vintage Garagiola, analyses of player tendencies mixed with colorful anecdotes, both essential to an informative, entertaining broadcast.

• Here’s Ted Lyons, a Hall of Fame pitcher, describing Stan Musial’s unusual batting stance: “Stan looks like a kid peeking around a corner to see if the cops are coming.”

• Here’s why Gil Hodges excelled at first base: “His hands are a legend. The spread from thumb tip to little finger tip is eleven and three quarter inches…. (H)e would catch the ball barehanded except that Hodges doesn’t want to go against tradition.”

• Here’s what it was like to catch behind Henry Aaron: “Don’t know to this day if he has a voice. Never said anything to the umpires either. Gave you the impression hitting of the fellow who just happened to walk into the batter’s box and says well throw it I’ll hit it. Very confident while hitting.”

Warren Spahn’s between-starts routine, Richie Ashburn’s home-to-first sprint speed, Ralph Kiner’s one-liner on “The Bob Hope Show,” Willie Mays’ relationship with Monte Irvin (“Willie idolizes Monte”) — it’s all there, and then some.

“It was such a great physical representation of how serious he was about his work,” Garagiola said. “It was accurate and it was funny. It was to the point, but it had color. It was just him in a book.”

And now it has a permanent home in upstate New York.

Gimme Five

Padres manager Mike Shildt on the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

Mike Shildt, the manager of the San Diego Padres, has always seen baseball as a vehicle for achievement in life. Years ago, he co-founded a mentoring program for sixth through ninth graders in his native Charlotte, emphasizing character traits that apply to both the sport and the wider world.

Advertisement

“I just believe in equality and opportunity,” he said.

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, the Kansas City treasure run by Bob Kendrick, matches well with Shildt’s ethos. He said he was honored and thrilled to be an ambassador for its “Pitch for the Future” expansion campaign, with the goal of building a 30,000-square-foot facility and campus. Ryan Howard, the former Philadelphia Phillies slugger, is also part of the effort.

Shildt is a baseball lifer. As a boy, his mother worked in the front office of the Charlotte O’s, then the Double-A affiliate of the Baltimore Orioles, and the ballpark was his playground and classroom. That experience molded Shildt, who offers five insights about why his support of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum is so meaningful to him.

It’s a duty — with no downside: “When I was in St. Louis, it’s close, and I went. I got a chance to connect with Mr. Kendrick and said, ‘Hey, can I help you with anything?’ And I’ve talked to Ryan Howard a handful of times. I’ve admired him for years as a player, and it’s really heady for me to work with him on this and to be a part of it. So I’m really excited to be doing my part to help with this expansion. It can only be good. I think the major-league game has a responsibility to appreciate and honor the past of a game that is beyond special.”

The clubhouse was an early education: “I grew up in a Double-A clubhouse and my world was opened up to players of all nationalities getting to participate in a great game. Victor Rodríguez, our hitting coach, was on the team in 1980; I was 12 and Victor was 18. But it opened my eyes. I grew up in a very diverse neighborhood, diverse in the sense of — I didn’t see skin color growing up. My best friends were Black, White, we all played together. They were just my buddies. Same thing in the clubhouse, I just saw ballplayers.”

The makeup of rosters is changing: “It wasn’t until I got older and I got out of playing and started getting into coaching that my eyes opened to the lack of opportunities being equally afforded to people in (challenging) socioeconomic situations, specific to the States — at least. From an African-American standpoint, the numbers continue to dwindle. As I’ve gotten closer to and in the big leagues, it’s my job to know where the players are coming from. … And you see the very, very stark decline in the African-American (presence) in the major leagues.”

Early exposure to baseball is key: “I started to see that trend when I was in the amateur side. I taught and coached baseball at an inner-city school, West Charlotte High School, from 1994 to ’96. And I had some amazing athletes that even at that time weren’t getting exposure to baseball. And then when they got exposure to it, they loved it. But they were so far behind on the technical side of it, and they had other opportunities in football and basketball, so that’s what they gravitated towards. So when I got to the On-Deck Academy, we made it nonprofit so we could create opportunities. But even then it was still hard, because there was just not the openness to participate.”

Advertisement

Remember the mission of the Negro Leaguers: “You know the old saying, baseball has been very good to me? I grew up with it. I got the opportunity and the blessing to be around it. I got a chance to meet my passion and my reasonable skill set at an early age. But I also know, without it, I shudder to think where I’d be. Without any clear direction economically or educationally growing up, I could have easily been spun out and who knows where my life could have taken me? Baseball is a vehicle for me that I’m grateful for, and I want to create those opportunities for everybody. So it’s really clear to me that we need to respect and appreciate the history of the game, which I value highly. So let’s preserve it, let’s honor it, let’s expand on it, let’s create more of an awareness to it. But let’s also think about what the Negro Leagues represented was opportunity for the next African-American player to play in the big leagues and that’s what I want to help with the museum as well: preserve the legacy and remember who paved the path, but what did they pave the path for? And that is more opportunity.”

Off the Grid

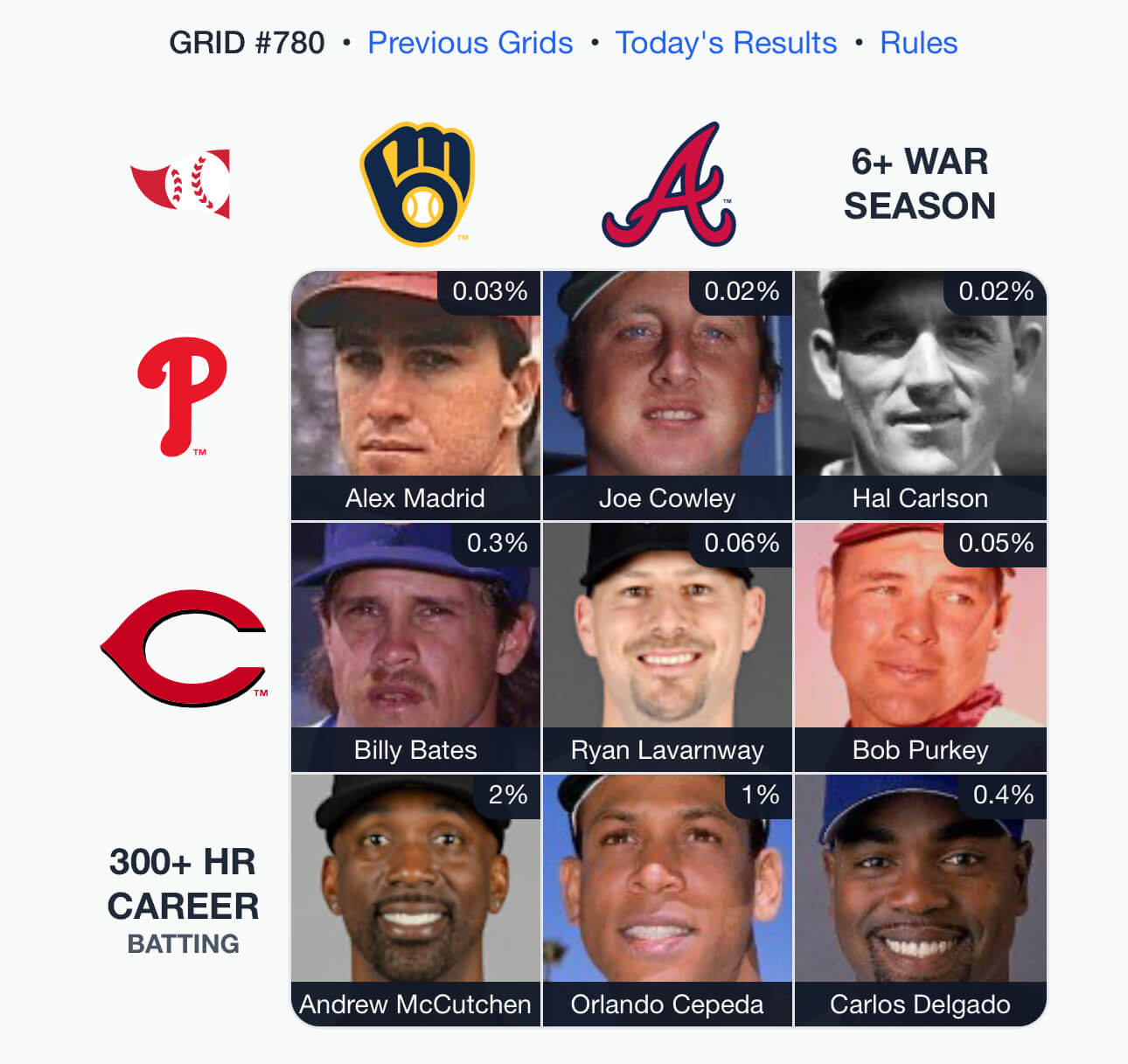

Bob Purkey, Reds 6+ WAR season

Bob Purkey made one World Series start, in Game 3 for the Cincinnati Reds in 1961. The Reds and Yankees had split in the Bronx, and Purkey pitched seven strong innings to put the Reds up, 2-1, entering the top of the eighth.

These days, he probably would have been replaced by a reliever. Back then, Purkey kept on rolling — until a pinch-hitter, Johnny Blanchard, smacked a game-tying homer with two outs in the eighth.

The Reds never led in the World Series again. Roger Maris, coming off his then-record 61 homers in the regular season, beat Purkey in the ninth with his only home run of the series. Two blowout wins later, and the Yankees were champions.

Purkey, at least, followed up that letdown with his best season, going 23-5 with a 2.81 ERA in 1962. With a National League-best 7.3 pitching WAR, he qualified for Wednesday’s Grid as a Reds pitcher with a 6-WAR season. By Baseball Reference’s formula, Purkey was worth nearly two more wins than Cy Young Award winner Don Drysdale of the Dodgers, likely because Cincinnati’s hitter-friendly ballpark, Crosley Field, increased his degree of difficulty.

As a young pitcher with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Purkey had learned a knuckleball from Branch Rickey, the team’s celebrated general manager. But the fateful October homers both came off sliders.

“Blanchard hit a mistake,” Purkey told reporters later, “but I don’t think Maris did.”

Classic clip

George Wendt starts the “We Will Rock You” chant on “Cheers,” 1990

When Norm Peterson wrote a letter, he once explained, he always signed off the same way: “I hope the Red Sox win the pennant.” When a new bartender told the gang that he rooted for the Cubs, Norm told the guy he was one of them. The bartender was confused until Norm clarified things. “We’re all losers!” he said.

Advertisement

But Norm’s greatest contribution to baseball started from a simple tapping of a pencil. The “We Will Rock You” cold open, from a Feb. 15, 1990 episode, has played on stadium scoreboards ever since.

Fun fact from producer Dan O’Shannon, as told to writer (and former MLB broadcaster) Ken Levine in an old blog post:

“When we shot it, we weren’t intending to fade out during the song. Instead, the song just sort of peters out, and that’s when Cliff comes bursting in singing “We will rock you,” too late to join in. When we looked at it in editing, it didn’t seem all that funny, so (we) decided to cut out early.”

Enjoy — and raise a glass for the real Norm, the great George Wendt, who died this week at age 76.

(Top photo of Rhys Hoskins: Jason Miller / Getty Images)

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.