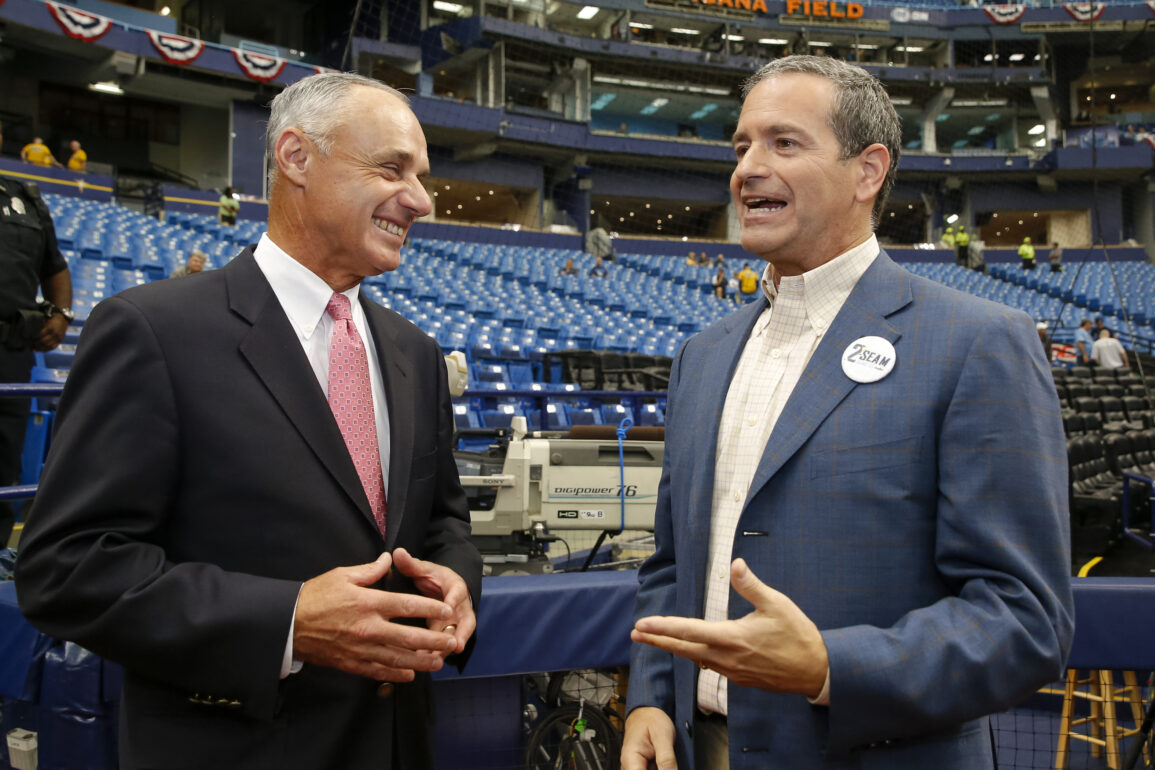

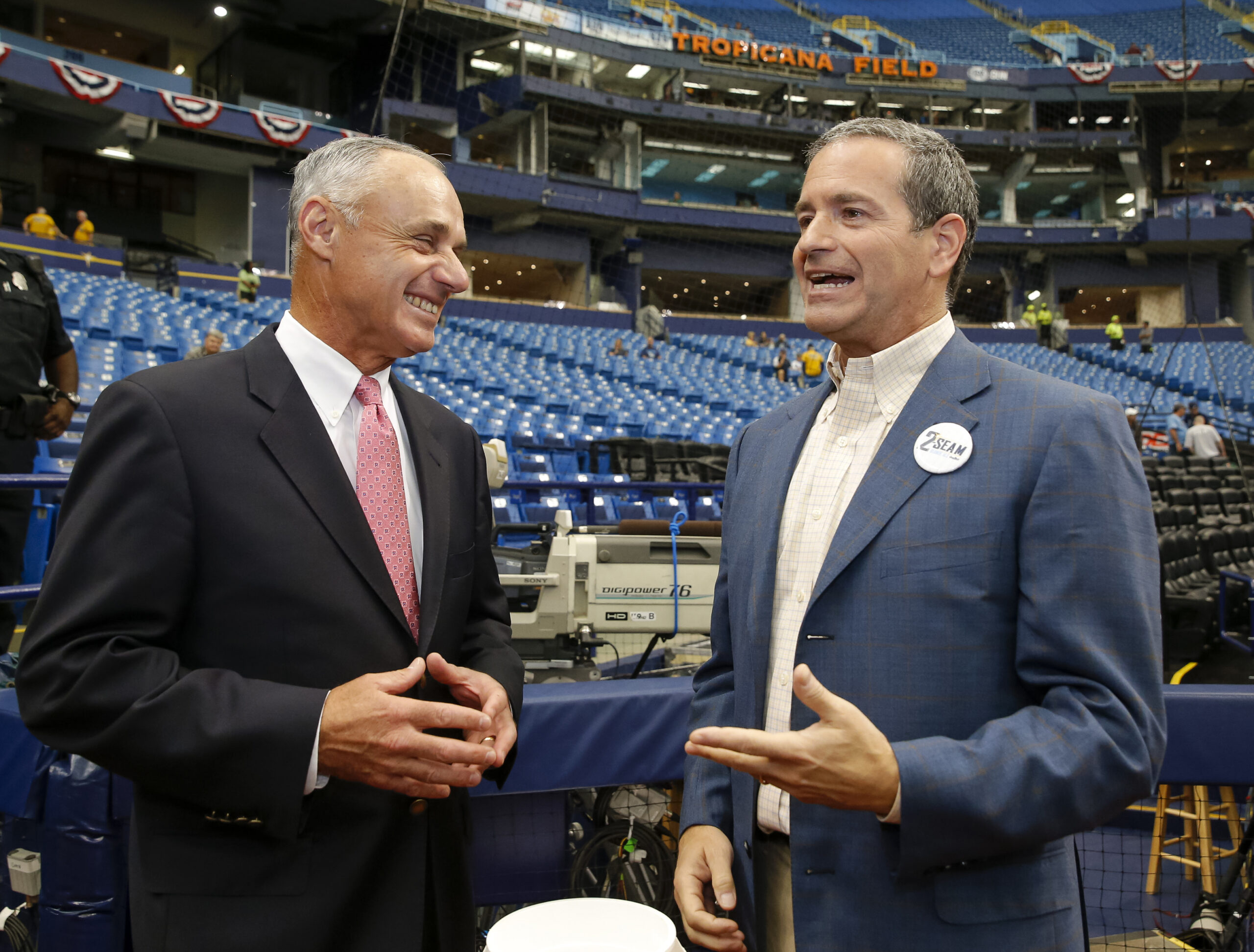

It is not easy to wade through this sentence without whiplash: “As he considers walking away from a stadium deal in St. Petersburg, Fla., Tampa Bay Rays owner Stu Sternberg is being pressured to sell his team by MLB commissioner Rob Manfred and some other owners.”

Not that it’s badly written—as constructed by Evan Drellich of The Athletic, it’s perfectly understandable. What gives it that special feeling of traumatic brain injury is the idea that Rob Manfred, or any commissioner, would pressure any owner to do anything, ever. That’s just not what commissioners do, because the first law of capitalist relationships is in force here: “Those who pay the salary give orders to those who receive it.” And since the argument into which Manfred has allegedly insinuated himself involves hundreds of millions of dollars, the idea of “pressure” is essentially unfathomable. In other words, “What?”

This situation requires a brief explanation. The Rays have wanted a new stadium to replace Tropicana Field, the pizza oven-shaped mausoleum in which they’ve played their home games for since entering the league in 1998, but negotiations between Sternberg and the politicians of Pinellas County (which includes St. Petersburg) have been thorny. That situation became more complicated after Hurricane Milton destroyed the roof of the Trop. The Rays, a.k.a. Sternberg, were supposed to come up with $700 million to build a new stadium, but are claiming that a delayed county vote over how much the citizens could be expected to contribute to a stadium project, given that the rest of the county was also ravaged, has led to increased stadium costs that the team should not be expected to/would not cover. There is a March 31 deadline that most people believe Sternberg will ignore as part of his bold strategy to strongarm his way to another town. This is known to chess aficionados everywhere as the Fisher Gambit.

So Drellich did some delving and came up with a story laying out the postulate of simultaneous owner and Manfredial pressure on Sternberg to either do the stadium deal as is or get out—in this case by selling the team to one of a number of potential buyers, a cohort including the DeBartolo Family, which owns the San Francisco 49ers and Leeds United. The DeBartolo in question here is Eddie Jr., who owned the 49ers until he got sideways with Louisiana politics and lost the team to his sister Denise. The presence of one of America’s baronial sports families is not surprising, really. It’s the Manfred part that is, with all due respect to Drellich, so impossible to parse. Here are some follow-ups that the presence of the commissioner—the highest-ranking, highest-paid, most servile employee of MLB’s owners—in all this:

- What makes baseball in Tampa so special that an owner could be pressured to sell by his fellow magnates and oligarchs, let alone their well-compensated night manager?

- What did Sternberg do to get his partners to turn on him when lousier owners have been allowed to skate cheerfully from blunder to blunder?

- Where was this concern for local governments and beleaguered citizens when John Fisher was poisoning his team in Oakland and is now subtly doing the same in West Sacramento with even less provocation? Did giving that atrocious corporate behavior and great steaming incompetence a mulligan cause Sternberg’s case to become so acute?

- When did Rob Manfred start to get so chesty to his bosses about so much as a stick of gum?

It’s the last one that is most confusing. Manfred’s job has always been to take the side of his owners in any issue that involves the exchange of money, because that is the job of every commissioner in every sport. Protocol demands that Manfred stand in front of Sternberg to catch whatever arrows come back his way, unless…

…Unless, that is, more powerful owners than Sternberg have decided he is screwing up relations with the politicals of a town/market that they want to keep close to their collective be-suited bosom. In that case, and we would posit in that case alone, Manfred would be fulfilling his broader mandate as the sport’s butler without portfolio by publicly turning on one of his many demanding bosses. Those bosses already have, in the Phantom Zone Athletics, a damaged franchise stuck in Yolo (yeah, that’s the name) County without a firm exit date due to their purposeful ignorance and malign neglect; maybe they just don’t want the headache of another such limbo franchise when the payoff is not Las Vegas but Montreal, or Louisville, or Pahokee. Maybe the only difference between the A’s and Rays is that the A’s were 13 miles by car from the San Francisco Giants while the Rays are 204 miles away from their partners in budget-conscious baseball operations in Miami.

These are all postulations soaked in speculation, and they all hinge on the notion that Rob Manfred is taking sides on the Tampa problem that are in opposition to Sternberg’s position. It also assumes that the other owners think Sternberg is being unreasonable to the city and county, which is preposterous on its face; being unreasonable to the cities and counties in which their teams are located is something like the signal value of this class. Additional complicating factors, as Drellich spells out, are the unpleasant labor negotiations coming next year, as well as resentments over the revenue sharing money that the Rays get for being the Rays, which is to say reliably much cheaper and a bit sharper than other MLB organizations. Maybe this is the start of the next phase of late-stage capitalism in baseball, or everywhere—owners eating each other over shares of a diminishing cash pie.

For the moment, though, the idea that Rob Manfred is taking sides against one of his 30 overlords on any topic is simply too improbable, not to mention delicious, to seriously conceive. Bobbleheads generally nod up and down, not side to side, and you just don’t argue with those physics.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.