Chicago Cubs starter Cody Poteet knew exactly what pitch he wanted to uncork to Los Angeles Dodgers slugger Max Muncy: a fastball down and away.

But as the ball left his hand — in the first inning of the first game of spring training Feb. 20 in Arizona — it drifted toward the inside corner, off target. Poteet’s catcher, Reese McGuire, had to reach back across his body to get it. Due to the slight location misfire, McGuire couldn’t present the ball the way he wanted, and the umpire made his decision. He called the pitch a ball.

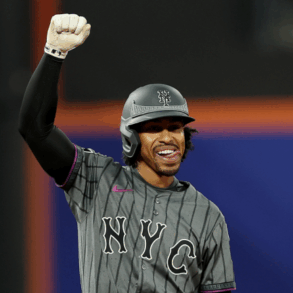

In every other game in Major League Baseball history, dating back to at least the 1880s, that call would have been indisputable and final — the end of the discussion. But today’s game isn’t anything like the one that was played in the 1880s — or in the 1980s, for that matter. Poteet didn’t have to accept the umpire’s opinion, and he didn’t. Utilizing new rules being tested at spring training this year, Poteet challenged the call. And he won his challenge moments later, when an array of cameras positioned around Camelback Ranch stadium, and an intricate computerized system, revealed the true location of the pitch to everyone present.

It was a strike.

“You feel like you made history?” a reporter asked Poteet after he was pulled from the game. He was standing in a media scrum at the time, and everyone laughed at the question. But Poteet — a 30-year-old pitcher with five career wins to his name and limited Major League experience — had to admit that, yes, he did feel like he made a little history, and he wasn’t going to apologize for it.

“Every strike matters,” Poteet said.

ANY BASEBALL FAN would agree with that sentiment: One strike can alter a game. But last week’s developments — Major League Baseball’s test of the automated strike zone, and the possibility of this rule change taking effect in regular season games as early as 2026 or ’27— has rankled one stubborn demographic: the baseball purist.

In fairness, these people have suffered a lot of late. Over the past few years, in an effort to shorten games and improve the pace of play, baseball commissioner Rob Manfred has ushered in a rule-change revolution that has included pitch clocks, larger bases, limits on pickoff moves, and the banishment of a defensive formation called the shift. And predictably, traditionalists have raged, shouting at both Manfred and the clouds.

“I think that’s the biggest battle that baseball has had, the purists fighting back on everything — me being one of them,” says Anthony Sprague, a former college pitcher who is now the general manager of the Buffalo Bisons, the Triple-A affiliate for the Toronto Blue Jays. “I was probably against 80 percent of the things that they rolled out.”

Now Sprague and others are willing to confess something that’s hard for a purist: “I was just so wrong,” Sprague says.

The big screen at Camelback Ranch stadium in Glendale, Arizona, shows a replay using the ABS system during MLB‘s first spring training game on Feb. 20.

Ashley Landis/AP

Fans and players alike have taken to the pitch clock, the larger bases, and the other rule changes that baseball implemented at the Major League level last year. And this success has given the game a certain amount of confidence, even swagger, as it considers its latest radical experiment: the Automated Ball-Strike challenge system, or ABS for short.

Major League Baseball rolled out the system last week at 13 spring training ballparks in Arizona and Florida, where it will be tested in roughly 60 percent of spring training games this year. In the test games, each team will get two challenges. But calling it a “test” doesn’t capture the epic road that baseball has traveled to get to this point. The so-called automated zone didn’t begin last week at spring training; it began almost six years ago, on a warm summer night in York, Pennsylvania, at the Atlantic League’s midseason all-star game.

It wasn’t the sort of event that would typically attract much attention. The Atlantic League is an independent operation, which at the time had just eight teams. The game that night featured players from the Long Island Ducks, the New Britain Bees, and the Sugar Land Skeeters, among others. Not a single player on the field was bound for fame, and the crowd in the stadium fit the moment. About 6,000 people attended.

But Morgan Sword, then Major League Baseball’s executive vice president of economics and operations, made sure that he was one of them. He wanted to be there to get a hands-on look at a new experiment that MLB was testing, with the Atlantic League’s cooperation, for the first time: balls and strikes not called by umpires, but by an elaborate system of powerful cameras, fiber-optic cables, servers, and software that could track each pitch and tell the ump what to do.

That night in the ballpark, Sword expressed optimism in his remarks to the media. He said it was an exciting night for baseball, historic even. But privately, he and others at Major League Baseball soon had concerns.

“The first thing we realized in the Atlantic League was that the rule-book strike zone is not a good strike zone to use,” Sword tells me. “Because if you really call it honestly — the way the rule books tells you to — there are lots and lots of pitches that are technically strikes that nobody would ever think are strikes.”

Breaking balls that clipped the front edge of the designated zone and bounced onto the plate were called as strikes. Curveballs at players’ armpits, breaking 12-to-6 and touching some piece of the back end of the zone, were also called strikes. Players quickly got angry. “You could see that everyone was sort of uncomfortable with the zone that the system was calling,” Sword says. At one point, sometime later in the Arizona Fall League, Sword recalls, a player even argued with the computer. “We had a player actually turn around and yell at the radar.”

But instead of giving up, baseball officials went to work. They kept testing at the minor-league level, tweaked the system, responded to feedback, endured many failures, persevered, and pulled off the most unlikely feat of all: They have made some baseball purists automated strike zone-curious. Even old-school managers whose careers in baseball date back five decades couldn’t wait to see the cameras and computers make the calls last week.

“I’m looking forward to watching it,” Texas Rangers manager Bruce Bochy, who made his minor-league debut with the Covington Astros in the Appalachian League in 1975, told me at MLB’s media day two days before that first Cactus League game. “I think it’s going to be a lot of fun for the players. We don’t know what’s going to happen, but we get six weeks to take a look at it. Then we’ll all have our comments and debate about whether it should stay in the game. But I think it’s something that could happen — I do.”

Like any great baseball story, the narrative around automated balls and strikes is an underdog tale. It required a comeback. It needed late-inning heroics. It couldn’t have happened without a leader like Manfred willing to take big swings, at incredible risk to himself. And like the very best baseball stories, the man in the spotlight in the crucial moment wasn’t on anyone’s lineup card. He wasn’t a star. Morgan Sword didn’t even play college baseball.

Now, Sword and a team of people in MLB’s front office are poised to change the game forever. They can track balls and strikes with an absurd level of precision — within the width of an M&M. They have defined a rule that fans, players, managers, and umpires have been arguing about for roughly 140 years: the strike zone. And they have come as close as anyone ever has to answering the most unanswerable question in the world’s most philosophical sport: What is the strike zone, anyway?

THE STRIKE ZONE IS currently defined in the Major League Baseball rule book as the depth and width of home plate — 17 inches in each direction — and the vertical distance between the midpoint of a player’s torso to the hollow just below his knees. But this zone has changed over the years. At one point, in 1950, the American League and the National League didn’t agree on how to define it. Sometimes, it morphs over the course of a game. In a blowout, the zone gets big; in a close game with high stakes, the zone gets small. It can even, some hitters contend, change based on whether an ump likes them or not.

Anyone who’s ever thrown a pitch or swung a bat knows that the umpire decides in the end — and those decisions have felt arbitrary and highly personal at times. Umpire Lee Weyer had a certain zone (huge). Umpire Dutch Rennert had a different zone (small), and umpire Eric Gregg’s zone was wide, just like his ample waist. “I can remember when the plate could get pretty damn big,” says Terry Francona, the manager of the Cincinnati Reds, who played in the 1980s and had to negotiate the whims of these umpires. “You better swing, but you knew that.”

In the past two decades, Major League Baseball has gone to great lengths to establish a more consistent zone. Still, there are arguments and misses. One Boston University researcher found in recent years that home plate umpires miss the call roughly 20 percent of the time. These kinds of mistakes don’t just affect games; they can alter careers for young players trying to make a roster. And hitters say that the umpire’s job is only getting harder. “That’s the problem when you’ve got 100-mile-per-hour pitches coming in with movement,” says Kiké Hernández, a 12-year veteran with the Los Angeles Dodgers. “As a human being, you’re supposed to sit behind the plate and guess where that pitch is going to break to or move to, and you don’t even have a second to decide whether it’s a strike or a ball. I think it’s a really hard job.”

From the moment Rob Manfred took over as commissioner in 2015, he pledged to use technology to help baseball, and reporters asked him right away if he might employ computers to improve the ball-strike situation. Manfred’s answer at the time was simple: No, not yet. He was focused on bigger problems — bloated game times and the slow pace of play — and he believed that there were limitations to what the technology could do at the time.

But by the summer of 2019 — the season of the Atlantic League tests — that was changing. And the next two years ushered in three developments that would alter the course of baseball history. The league partnered with Hawk-Eye Innovations, the company that developed the system used to track serves, shots, and volleys in professional tennis. Manfred promoted Sword to be executive vice president of baseball operations, overseeing the raft of potential changes that the league was considering, including automated balls and strikes. And Major League Baseball itself changed. It assumed control over the minor leagues. Manfred could now test any rule he wanted in the minors. It had become a laboratory and Sword, just 35 years old at the time, had become one of its chief scientists.

Morgan Sword, MLB’s executive vice president of economics and operations, has been leading the league’s testing and implementation of ABS since 2019.

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

SWORD UNDERSTOOD THE strike zone; he was a catcher in high school. But he acquired his most important skills off the field, in college. As a freshman at the University of Virginia in 2003, he applied to be a student manager of the baseball team. “I was fresh off reading Moneyball,” Sword recalls. “And I was just fascinated by the whole premise of the book.” He wondered if he could be like Billy Beane — the real-life protagonist at the heart of the narrative, who used a data-driven approach to reinvent the Oakland A’s — and utilize his problem-solving skills to work in baseball.

Brian O’Connor, Virginia’s head coach, hired Sword and initially put him on the usual tasks: laundry and field prep. But O’Connor soon realized that Sword was different than most 18-year-olds. “You could tell quickly that he could handle more,” O’Connor says. And O’Connor gave it to him, he says, until Sword was handling budgets and scheduling — tasks that student managers typically didn’t assume.

After graduation, Sword’s résumé impressed Manfred enough that he hired him at Major League Baseball. Manfred liked Sword’s “quantitative” approach and didn’t hesitate to put Sword in charge of the rule-change operation. He believed in Sword and his young team of front-office free thinkers. It included Joe Martinez, a former Major League pitcher in his late thirties; Reed MacPhail, a fourth-generation baseball man in his early thirties; Theo Epstein, the architect of World Series miracles in Boston and Chicago, then a consultant for baseball; and countless data-crunchers and analysts. Sword says they looked at the strike zone that was being used in the Atlantic League and elsewhere and quickly came to a conclusion: “The geometry’s not right.”

Maybe they needed to stop thinking about the zone as a three-dimensional box, they said. Maybe it was a linear plane, floating vertically in space over the plate. Or maybe it was two vertical planes, one near the front of the plate and one near the back, and the pitch had to pass through both of them. Or maybe it was a three-dimensional box with the front portion chopped off, to prevent breaking balls in the dirt from being recorded as strikes. “We talked about a bunch of things,” Sword says, and finally settled on a single linear, vertical plane, bisecting the plate at the midway point. A pitch would have to pass through this zone to be called a strike.

But that still left a lot of problems to solve. Sword’s team still had to determine the best height and width of the automated zone — a process that required years of trial and error. At one point, they set the zone’s width at 21 inches — four inches wider than the plate — and strikeouts surged. At another point, they set the height of the zone too low, and pitchers complained. And then there was the issue of how to employ the technology at scale. Justin Goltz, Hawk-Eye’s commercial director for U.S. business, says that a stadium installation can cost up to $500,000 dollars, involving eight to 12 cameras, a half-mile of fiber-optic cables, staffers who need to check the equipment before and during games, and computer servers capable of processing the images in less than 200 milliseconds — roughly the blink of an eye.

The good news was, Goltz knew it would work. “It’s so accurate,” he says, “it’s impossible to improve upon the margin of error, given the testing mechanisms that exist today.” The bad news was, Major League Baseball wasn’t sure how best to use it. For two years, the league went fully automated. Under this system, the Hawk-Eye technology would call every pitch, every time, feeding the call to the home plate umpire through an earpiece.

This system gave birth to a term that Manfred, Sword, and the umpires themselves didn’t appreciate. Reporters dubbed the officials “robo-umps” — a moniker that diminished the umpires’ craft. More problematic, perhaps: Most players in the minor leagues didn’t like the fully automated option. Especially not catchers. Under full automation, catchers had no need to frame a pitch — a skill that is fundamental to the art of the position, making a pitch “appear” to be a strike by the way they caught it or held it in their glove. The automated system didn’t care about art. And baseball ran into other unexpected issues. Jack Dreyer, a pitcher who played last season with the Dodgers Triple-A affiliate in Oklahoma City, says he was in a game against Sugar Land last May that went sideways because the system was in charge instead of a human umpire.

“A position player came in to pitch in a blowout game and he was just lobbing balls in there,” Dreyer says. If a human umpire were behind the plate in this moment, the zone would have expanded, and everyone could have gone home. But because the system was making the calls, the umpire couldn’t do anything. “His hands were tied,” Dreyer says. The final score was 22-3, and the game went on forever.

Thanks to feedback like this, baseball began testing a system that was a little different. In this format, the Hawk-Eye technology was still tracking every pitch, but teams had to use a challenge if they wanted to question a call. Teams got two or three challenges per game, a model that proved to be far more popular. Minor-league managers and players can all point to an exact moment when a game changed on a challenge.

A network of cameras like this one (at minor-league Coca-Cola Park in Allentown, Pennsylvania, in 2023) monitor pitches as part of the ABS challenge system.

Rich Schultz/Getty Images

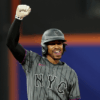

In a Triple-A game in 2023, the Buffalo Bisons beat the Syracuse Mets in a comeback rally in the ninth after batter Spencer Horwitz challenged a called strike, won the challenge, stayed at the plate, and singled to extend the rally. Horwitz, who is now with the Pittsburgh Pirates, remembers being excited that day. “There’s a feeling in the box when you challenge one,” Horwitz says. “You’re like, ‘Ooooh, maybe it’s not there or maybe it is?’” Michael Toglia — a player for the Colorado Rockies who’s logged some time in the minors in recent years — says that when he wins a challenge, it alters everything for him. “It changes your whole day,” Toglia says. “You sleep better.” And Chad Tracy, the manager of the Worcester Red Sox, knows the feeling. His team won a game against the Norfolk Tides in 2023 on back-to-back challenges in the ninth.

“We struck out Daz Cameron,” Tracy recalls, play-by-play style. “He challenges the call. We think the game’s over. They overturn it, so now we have to continue pitching. We struck him out again. He challenges it again. This time, ABS confirms it was a strike.”

The game was over, and in Tracy’s memory, the crowd went wild.

“It was intense,” he says, “because everybody thinks the game’s over — twice.”

BASEBALL PURISTS CAN — and will — debate whether endings like these are good for the game. And there are many other questions that still need to be answered, including what dimensions are best for the automated zone. At spring training this year, baseball is testing a version based on the batter’s height, which required every single position player to be measured by independent evaluators last week. Sword is interested in getting players’ feedback about this zone, and he says that their notes could force him and his team back into the lab for more tinkering.

But Manfred knows how he feels about the technology in general. “I think that when you have technology like this,” he tells me, “you kind of owe it to your fans to try to get the call right.” He believes the ABS challenge system “would be a material improvement for the game,” and he’s eager to see how it works during spring training.

On the day of the first game last week in Arizona, the players seemed excited, too. Shohei Ohtani, the most famous baseball player in the world, said through his interpreter that he couldn’t wait to try it from the batter’s box — and the mound. “I’m really looking forward to being able to experience it,” he said, “as a pitcher and a hitter.” His teammate, Hernández, said he hopes it could be introduced in regular season games as early as next year. “If I’m doing half of my job right — which is to take a ball — I want to be rewarded for it,” he says.

When Cubs pitcher Cody Poteet used that first-ever ABS challenge that day, the events that unfolded took about 10 seconds. The Hawk-Eye technology churned out the image. The stadium broadcast a rendering of the pitch onto the big screen at the ballpark, and everyone learned what Poteet himself already knew: His pitch was a strike. A 1-1 count became 0-2, and Muncy struck out two pitches later, when Poteet put another fastball in the same spot. It was just spring training, a scrimmage, but it had mattered. That one call, Poteet later said, “totally changes the dynamic of the whole at-bat.”

The game quickly got away from the Dodgers. The Cubs went up 12-3 and the crowd had thinned out a bit by the late innings when a Cubs player issued a second challenge — and lost. But Morgan Sword was still there, watching from behind home plate, and he felt like what he had seen was a good start. The technology had worked and not much else had changed — or maybe everything had. Sword had just spent an afternoon at a ball game, with a pitch clock, bigger bases, and calls that any player could overturn — if he knew the strike zone.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.