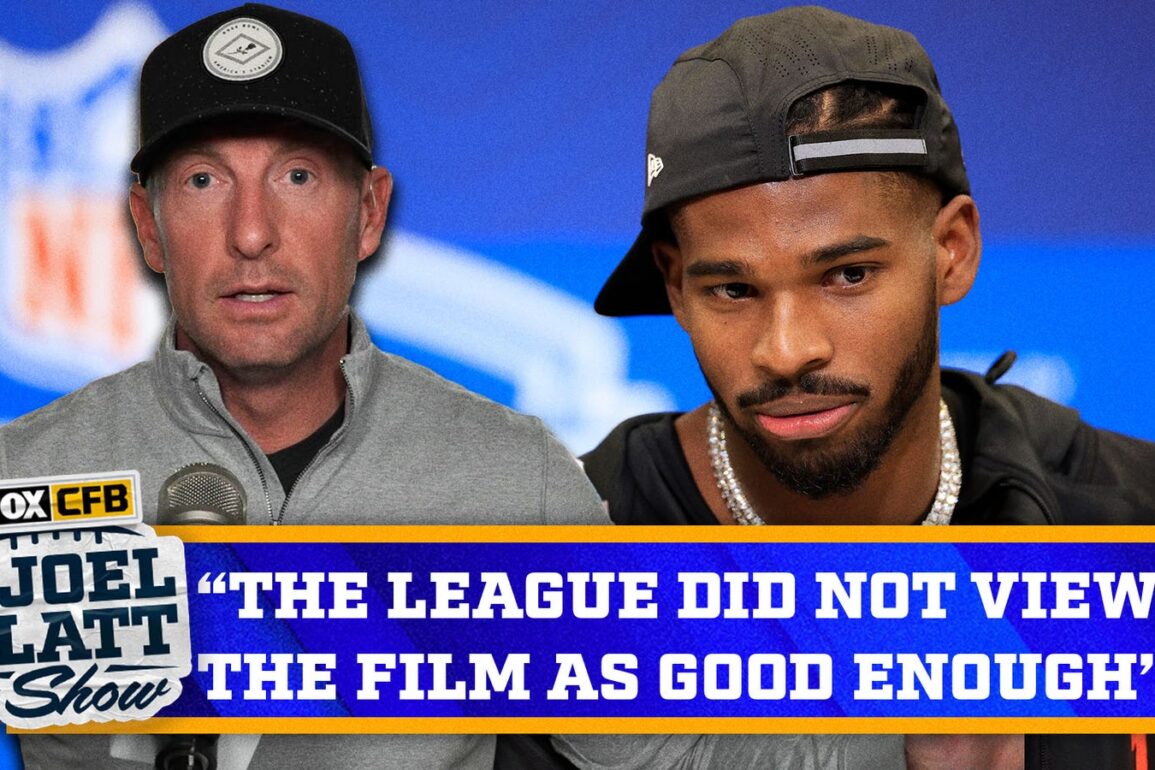

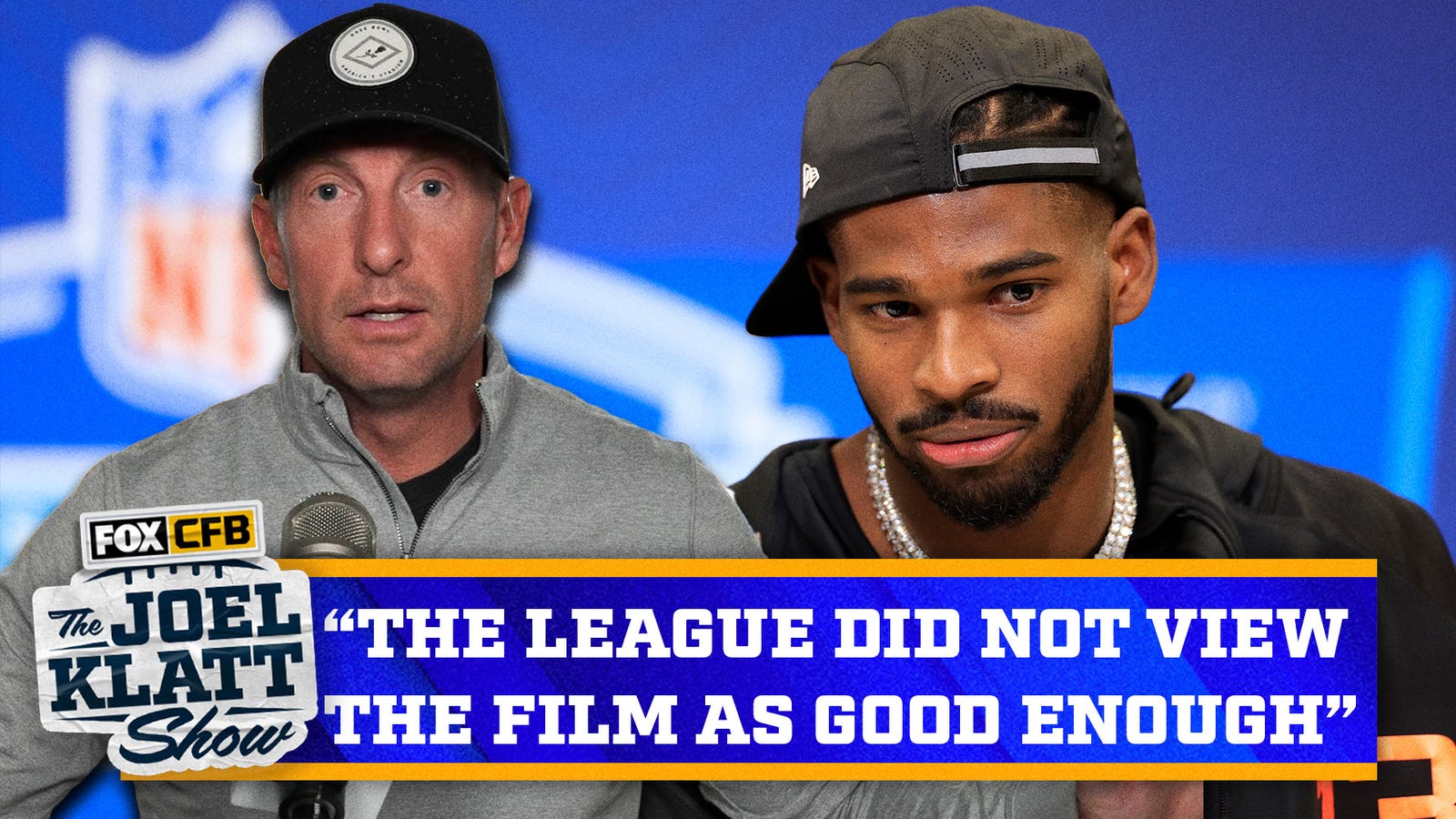

Two weeks ago, as the 2025 NFL Draft transitioned from Day 2 to Day 3, the parallel slides of former Colorado quarterback Shedeur Sanders and former Texas quarterback Quinn Ewers began to dominate the discussion surrounding this year’s event — even as their respective freefalls were sorted into wildly contrasting pools of logic.

The former, who ultimately went to the Cleveland Browns with the 144th overall selection, was knocked for the way he and his famous family handled portions of the pre-draft process, including formal interviews with several teams around the league that were reportedly less than impressed. The latter, who would eventually be taken by the Miami Dolphins with the 231st overall pick, was dinged for his potentially worrisome injury history and a career that had been solid if unspectacular across two seasons as the Longhorns’ starter, though both campaigns included trips to the College Football Playoff, the first such appearances in program history.

But from a purely numerical perspective — speaking only of draft capital invested — the NFL’s message to both was unflinchingly clear: Neither player was viewed as a likely starter at the game’s most important position; otherwise, had the inverse been true, both signal-callers would have been drafted far earlier.

Instead, Sanders and Ewers became two of the more high-profile prospects to embody a recent draft trend that, over the last two years, has seen franchises largely eschew selecting quarterbacks in the middle rounds. An examination of draft data from the 21st century shows that an average of 3.75 quarterbacks per year were selected in rounds two, three and four between 2000 and 2023. Since then, however, the number has plummeted to just three quarterbacks taken in that same range over the last two drafts combined, including no such selections in 2024 when more than 130 picks elapsed between former Oregon standout Bo Nix at No. 12 overall and Spencer Rattler, the enigmatic South Carolina passer, at No. 150 overall.

ADVERTISEMENT

The sample size is small enough so that labeling the recent evaporation of middle-round quarterbacks as a legitimate philosophical shift by front offices would be entirely premature. But that hasn’t stopped people in various corners of the sport from attempting to find a correlation between what’s happened over the last two drafts and the evolution of football at both the collegiate and professional levels. One of the biggest questions they’re now pondering involves quarterbacks like Ewers, who could have stayed in school for another season, and whether players who are unlikely to be drafted in the first or second round — but who still have eligibility remaining — will stave off turning pro more frequently than they did before. By remaining in school, those quarterbacks have the potential to secure what might be significantly larger paydays through NIL and, eventually, revenue sharing than the modest, non-guaranteed contracts they earn as Day 3 draft picks.

“You see some of that as the money goes up, right?” said one high-ranking executive from an NFL front office. “Because the money is more this year than it was last year, more last year than the year before. So I think that may become a thing more as we march forward because the money is just going to continue to grow to a point where these guys have real options financially if you’re not going to be a bonafide first-round pick.”

Cam Ward of Miami (No. 1 overall), Jaxson Dart of Ole Miss (No. 25 overall) and Tyler Shough of Louisville (No. 40 overall) were the only quarterbacks selected in the first two rounds of this year’s NFL Draft, which means the other 11 signal-callers who were eventually chosen all landed in rounds where career backups and third-stringers are most commonly produced — and the non-guaranteed contracts they’ll sign reflect that standing. Sanders, who went in the fifth round, is expected to ink a four-year deal worth approximately $4.6 million, according to projections for this year’s NFL rookie salary scales. While former Indiana standout Kurtis Rourke, who was the first quarterback selected in the seventh round, is likely to sign a four-year deal worth roughly $4.3 million.

Most of the quarterbacks selected on Day 2 and Day 3 of this year’s NFL Draft had already exhausted their collegiate eligibility, leaving them with no other option than turning pro. Sanders, who played two years at Jackson State and two years at Colorado, was firmly in that camp. As was former Oregon quarterback Dillon Gabriel, the No. 94 overall pick and Sanders’ future teammate in Cleveland.

But those constraints didn’t apply to former Alabama quarterback Jalen Milroe, who was taken No. 92 overall by the Seattle Seahawks. Milroe had one more year of eligibility remaining and certainly would have commanded a lucrative NIL package from either the Crimson Tide or another playoff-caliber program via the transfer portal. Instead, he is expected to sign a four-year deal with the Seahawks worth $6.26 million in total with a first-year salary of approximately $840,000 — a far cry from the reported $4 million NIL deal secured by former Georgia quarterback Carson Beck when he transferred to Miami this offseason.

Nor did the eligibility concern apply to Ewers, a fourth-year junior who could have returned to Texas or entered the transfer portal ahead of the 2025 campaign. Reports surfaced in January that Ewers, who began his career at Ohio State, turned down an $8 million offer to transfer before deciding to turn pro. After slipping all the way to the seventh round, where he was the last quarterback taken, Ewers’ first contract with the Dolphins will be worth approximately $4.33 million over four years with very little guaranteed money.

“Maybe some school would have given him a few million,” said one longtime NFL agent who was granted anonymity to speak freely. “But he’s still in Arch Manning’s shadow [anywhere in college football], and he’s been in school for so long. Does he really think he can improve his NFL game? Now, if you gave him a crystal ball and he knew he was going to be a seventh rounder, would he have made a different decision? Maybe. But you’re saying do you think we’re going to see the elimination of the middle-class quarterback, the second- and third-round quarterback? It depends what a player’s expectations even are.”

Deciphering those expectations, the agent said, involves answering some of the age-old questions that have swirled around draft prospects for decades: Has the player already earned an undergraduate degree? How quickly does the player need money to support himself and, potentially, his family? Is the player enjoying his collegiate experience and willing to leave that life behind? Other questions, like those involving personal insurance policies, are more nuanced and indicative of modern times: Can a player definitely find an insurance policy that will provide sufficient coverage if he suffers a career-altering injury while spending an extra year in college?

The calculus seems to be changing on the team side, too, with both collegiate personnel departments and professional front offices beginning to augment their outlooks for prospective quarterbacks. On the college side, where not a single third-year signal-caller entered this year’s NFL Draft, the pendulum that often swings between early playing time and year-over-year development seems to be hovering over the latter, especially when presented in tandem with NIL opportunities that aren’t tied to on-field production.

These days, a blue-chip quarterback prospect who develops into a viable Power 4 starter and spends four or five years in college can reasonably expect to pocket north of $5 million over his entire career, with some players skyrocketing toward eight figures and beyond. That’s a drastically different recruiting pitch from the days when coaching staffs would lure elite quarterbacks to campus with a vision of three years in college followed by early draft entry to maximize earning time in the NFL. An influx of personnel staffers with legitimate NFL backgrounds, like new Oklahoma general manager Jim Nagy, who was the executive director of the Senior Bowl and spent nearly 20 years as a scout, are now aiding players in the decision-making process.

Clemson’s Cade Klubnik, the No. 1 quarterback in the 2022 recruiting cycle, and Penn State’s Drew Allar, the No. 4 quarterback that same year, are two examples of juniors who could have entered this year’s NFL Draft but chose to remain in school for various reasons. Both will be well-compensated by their program’s respective NIL apparatuses for doing so and should be discussed as early-round picks in 2026.

“It helps in terms of putting together a financial package that makes sense for both sides,” said Cooper Petagna, who worked in recruiting departments at Michigan, Oregon and Washington, and is now a national recruiting analyst for 247Sports. “They can say, ‘Hey, this is how much guaranteed money you would make if you were a Day 2 draft pick, early Day 3 draft pick. You’re an all-conference, winnable-plus kind of player here. Here’s what we’d be willing to do for you, and it’s comparable. And if you come back, here are multiple examples of guys that have come back for one more year, put it on tape, and then have gone on to have more long-term success financially in the NFL as well.’

“So yeah, I think that’s going to be more a part of the game. I think the education will be more a part of the game. I think we’ve already seen this in the NBA as well as there’s been a trend of players coming back to school because of the compensation that they can have. And they can also benefit from a development standpoint, too.”

Ripple effects from that kind of recalibration will likely be felt across the NFL in the coming years, according to the front office executive, with the seeds of those changes already being planted throughout the scouting process. The advent of NIL means teams have a new data point to consider during the buildup to each draft, as scouts and general managers evaluate how top quarterback prospects handle lucrative paydays long before they’ve entered the league. Some evaluators have also begun placing more value on collegiate playing time and development in an era when NFL rule changes are increasing the longevity of quarterbacks. It’s no longer viewed as a massive red flag when prospects turn pro closer to their mid-20s, evidenced by the New Orleans Saints’ selection of Shough, who turns 26 in September.

All of which leads back to Sanders and Ewers, two players whose draft-weekend slides ignited wide-ranging conversations about the plight of middle-round quarterbacks. It’s too early to say whether this recent trend will stick around for good. But the money being thrown around in college football means there are far worse options than spending an extra year or two in school.

“I would not be surprised to see moving forward,” said the front office executive, “guys that are gonna be third- or fourth-round picks just stay in school, make a bunch of money and not test the waters.”

Michael Cohen covers college football and college basketball for FOX Sports. Follow him at @Michael_Cohen13.

Want great stories delivered right to your inbox? Create or log in to your FOX Sports account, follow leagues, teams and players to receive a personalized newsletter daily!

recommended

Get more from College Football Follow your favorites to get information about games, news and more

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.